Abstract

In Ulysses, we see a strong empathy and sense of duty, but which at times seems to develop a coldness and indifference to others outside of his desired goal. While this could create a less human and endearing character, the paradoxical nature of his responses to those he seems to love or care for creates a more human portrayal. In this, Homer delivers a means of understanding a long past culture. One that we can see is very different from our own. One that embraces aspects of violence and rapine that we like to believe are gone yet in times of war and violence remain close to the surface. Through Ulysses, we see a side of humanity that modern sensibilities would suggest has been expunged—yet, equally, one that in times of stress and anarchic conflict bubbles to display and foment past aspects of our nature.

Keywords: Ulysses, the Odyssey, comparative cultures.

Introduction

The adventures of Ulysses[1] represent a quest to return home and the hubris and all too human decisions that interfere with the said goal. Following a decade of battle at Troy, Ulysses spends another decade seeking to return home. As with many great contemporary novels and stories, the Odyssey captivates the reader as the protagonist experiences a series of trials and tribulations, including monsters, gods and alluring women.[2] However, through all this, it needs to be remembered that the greatest desire of the protagonist was to continually experience domestic bliss with his family and the management of his farm.[3]

Despite this, cultural differences exist, coupled with many similarities in how people act. For example, while Ulysses and Penelope share some common traits, they also exhibit vast cultural differences.[4] Understanding the work of Homer requires that we also seek to understand how individuals within classical Greece and before thought about different actions and activities.[5] It is necessary to contemplate the cultural differences between modern sensibilities and individuals from classical Greece to understand such work.[6]

The characters Ulysses and Penelope are equally cunning and sly.[7] While it is well-known that Ulysses is a “sly fox”[8], Penelope tricks the suitors for three years into waiting as she weaves us shroud for her father-in-law, Laertes, while unstitching it at night.[9] Their depiction in this myth creates the archetype of many subsequent stories. The narrator is devious, and Homer gives us a one-sided story.[10] Telemachus remains a youth searching for his father, too weak to take the mantle of controlling the household. Laertes wastes in sorrow for his lost and wayward son. The devoted servants Eumaeus and Euryclea demonstrate doglike loyalty. This story has become a universalised literary model and the foundational trope representing human exile and the process of discovery.[11]

The story has become so ubiquitous that the word “odyssey” has come to represent any long adventurous journey or even the development of a person through their life experience and career. James Joyce integrated the primary theme in the representation of the everyman in Ulysses[12]. Interestingly, Joyce used the lesser-known Greek name of Ulysses rather than the Odyssey representing the underlying discontent that separates the later Roman version of the story. The literary troops used throughout the Odyssey have come to represent stories of heroism and form the basis of many western gender roles.[13]

The Great Unknown

There is little historical evidence of the origins of Homer.[14] However, legends exist claiming that Homer was from Asia Minor, either from Smyrna or Chios, and an unsighted mendicant minstrel. The homeless nature of the Bard has been alluded to in the archaic verse:

Seven cities warred for Homer being dead,

who living had no roof to shroud his head.[15]

These “seven cities” of Chios, Smyrna, Rhodes, Salamis, Argos, Colophon, and Athens sought to claim Homer following his death.[16] Instead, as the teacher and bearer of cultural wisdom, Homer came to represent the underlying cultural tropes displayed across the Hellenic world. While these works were literary, the reverence held in ancient Greek culture mirrored the veneration of the Bible to many contemporary Christians. While not forming an orthodox body of work, Homer’s stories guided and transformed many aspects of Greek religion.[17]

The depictions of the gods came to form the foundation of many theological arguments. The popular view of Homer became one of wisdom and erudition. However, others, such as Plato, disputed Homer’s authority and influence.[18] While mythical, the Homeric age and the stories contained within Homer’s works hold a foundational grain of truth and historical truth. This early patriarchal tribal society depicted was of close kinship ties and family centred economies.[19] As an early Greek agrarian society, Homer represented an early society where the level of subsistence was low enough that the master of a household or community would often work alongside women and slaves.[20]

Myth in this form brings us knowledge that sometimes apocryphal contains descriptions of earlier governments and the relationships between people.[21] For example, representations of councils and nobles under the governance of a king provide insight into the various relationships between members of that culture. In addition, noting how kingship is not always hereditary and that the King was also a noble demonstrates the lack of modern hierarchy in power structures. Finally, Ulysses and Menelaus themselves represented royal lineages that developed as mayorial leaders of town size city-states.[22]

In the society of Homer, religious worship of the societies was conducted through a combination of liberation, sacrifice prayers and, in Athens, theatre.[23] In addition, through a process of feasting and storytelling, Homeric minstrels provided not only recreation but spiritual guidance.[24] The Iliad and Odyssey are premised on a story concerning the Trojan War, with the traditional fall of Troy or Ilium being represented as 1184 BCE. These legends have been demonstrated to coincide with the 19th-century archaeology by Schliemann. The Iliad concerned the tenth year of the war. The Odyssey represents the end of the war through the building of the Trojan horse through the return of Ulysses.[25]

The Fall of Troy

Ulysses is recounted in the narrative of the Trojan horse.[26] However, through proposing and implementing the strategy based on this deception, Ulysses demonstrates his profound cleverness. The horse provides the needed trick that enables the Greeks to enter and destroy Troy. However, the response that occurs when the Greek army sack Troy angers and repels even the gods.

Haft demonstrates that while Ulysses masterminded and directed the stratagem that ended the Trojan War, even this did not anticipate the scope of the desecration.[27] Despite the guilt over the sacking of Troy, the regret for the “killing, robbery and sacrilege”, Ulysses continues his recklessness cumulating in the slaughter of the suitors.[28] As Myrsiades demonstrates an examination of this topic, the response by Ulysses goes far beyond what is needed for honour or hospitality.[29] Yet, equally through Homer, Ulysses has gained a form of immortality despite rejecting Calypso’s offer.[30]

Are Heroes Heroic?

The modern-day representation of the heroic aligns with the moral good.[31] While Ulysses experiences a life of turmoil and tribulation, experiencing extraordinary events and places, he can hardly be seen to be morally upstanding.[32] In this, the requirements of epic narrative are fulfilled, but equally, the hero, while great, does not need to be noble or upstanding.

Ulysses is very different from a noble character of high tragedy and storybook adventure.[33] The foxlike wiles of this character differentiate him from many other heroes in that his main redeeming traits are based on a combination of tenaciousness and guile. Throughout the epic, Ulysses is referred to as suspicious, cautious and devious. Both Ulysses and his wife are clearly cunning and guileful.[34] Ulysses demonstrates little trust even to the gods. Those who constantly go out of their way to befriend and aid him find that he is not reciprocating what they provide.

The Goddess Ino provides him with a veil to save him from drowning. Yet, it is not until his raft is smashed into small pieces and he is near to drowning that he will trust even the gift of the Goddess.[35] He requires the nymph Calypso to swear that she intends no harm before he will take any action in going to sea. When returning to his home in Ithica, the changes over a decade led him to believe that the Phaenians had deceived him and delivered him to a different location. Even when Minerva tells him that he is in Ithaca, he refuses to believe, and she needs to correct him.[36]

“‘You are always taking something of that sort into your head’, replied Minerva, ‘and that is why I cannot desert you in your afflictions; you are so plausible, shrewd, and shifty.’”[37]

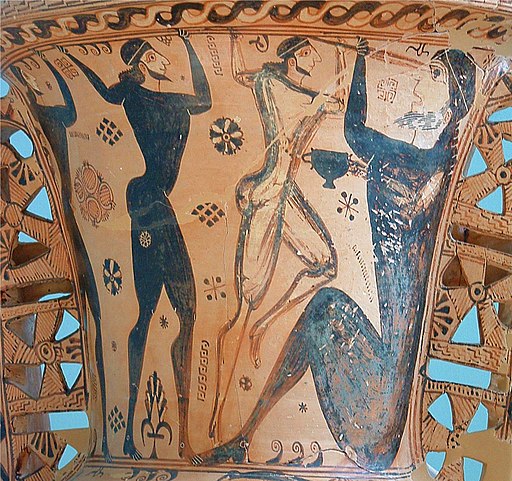

Homer’s heroes are also complex. They don’t fit a standard definition of a flat paper character. They are intricate and human. Unlike many modern romantic heroes, Homer creates a human and flawed character. While Ulysses is wily and at times seemingly predictable in his cunning, he is all too human and forgets prudence and restraint.[38] The capture of Ulysses and his men by the Cyclops demonstrates his cupidity. While having been counselled against action, at times, Ulysses will throw caution to the wind and as Circe notes;

“‘You daredevil’, replied the Goddess, ‘you are always wanting to fight somebody or something; you will not let yourself be beaten even by the immortals.’.[39]

There is a sense of duty and fate in how Ulysses approaches life. “But I must go, for I am most urgently bound to do so.”[40] Ulysses’ approach to problems differs significantly from how his son Telemachus reacts. While Ulysses is often brash, his son exhibits a meekness that is not fitting for a tribal leader. “No matter how valiant a man may be, he can do nothing against numbers, for they will be too strong for him.”[41] Ulysses often runs into trouble that exceeds his ability requiring the gods to step in and save him. The difference between father and son is marked and made clear throughout the epic.[42]

The Young Prince

Telemachus is a young, uncertain Royal who does not know whether his father is alive or dead.[43] In waiting, he sees suitors seeking his mother’s hand. Yet, he would see each of these men as inferior to any in his paternal line. They devour his birthright and act insolently. Yet, unlike modern princes such as Hamlet, no incestuous remarriage or family member seeks to usurp his position. Hamlet was angry at his mother, but Telemachus was merely irritated about the entire situation he faced.[44]

Hamlet faces phases of indecision and introspection. Through this, he accomplishes revenge at his own expense. Yet, Telemachus is indecisive without action. Further, he doesn’t even know whether Ulysses is truly his father, “it is a wise child that knows his own father.”[45] Whilst exhibiting a demeanour that is “brooding and full of thought”[46] with the melancholy of Hamlet and exhibiting deep pessimism, “I inherit nothing but dismay”,[47] his outlook differs significantly. Unlike Hamlet, he talks up to his mother’s suitors. As they resist him, he relents. He cannot act without Minerva’s constant goading in all of this.

Telemachus sees his sad estate as the only son of an only son who is of “a race of only sons.”[48] Hamlet wore a mask of insanity, but Telemachus exhibits a show of fragility and uncharacteristic and manliness.[49] While it is not possible to know whether either character was feigning the position of madness or vulnerability, Telemachus hammers home the point that “I shall either be always feeble and of no prowess, or I am too young, and I have not yet reached my full strength so as to be able to hold my own if anyone attacks me”.[50]

Each tragic Prince concludes by slaughtering their adversary. But while Hamlet is central to the story, Telemachus never quite manages to decide by himself, and his father’s return is central to his actions. In some ways, Hamlet acts through his father’s spirit or ghost but still maintains free will. On the other hand, Telemachus is a product of a society based on adherence to a belief in the fates and deterministic destiny. Because of this, Telemachus may be seen to merely enact the will of Ulysses.

Of Villains and Heroes

Modern concepts of the hero and villain have a distinctly different cultural base than those in Classical Greece. While the suitors seeking the hand of Ulysses’ wife loiter and abuse the rules of hospitality, we (of modern civilisations) could not justify murdering such a guest. Instead, Homer acts as the narrator, a neutral spectator. By doing this, Homer provides the suitors with an opportunity to talk and defend their activities. Of note, they contend that they are acting to compel Penelope, who is dilatory and who taunts each of them, to make a decision.

Heitman investigates the claim made by Eurymachos that Penelope’s actions in stringing along the suitors have harmed all of the Ithacan and families.[51] Eurymachos argues how interpreting natural signs may not be meaningful because we want them to be. “Many other birds who under the sun’s rays wander the sky; not all of them mean anything”.[52] Interestingly, Telemachus is young. Yet, while Ulysses exhibits qualities of the pre-classical King in the audacity and willingness to risk, Telemachus takes the position more aligned to an older man such as Ulysses’ father. The arguments of the suitors demonstrate this distinction.

But I will tell you straight out, and it will be a thing accomplished:

if you, whom no much and have known it long, stir up a younger

man, and by talking him round with words encourages anger,

then first of all, it will be the worse for him; he will not

on account of all these sayings be able to accomplish anything.

(Od. 2.187-91)

The suitors argue that it is Penelope and not them that are causing problems. If Penelope would stop acting cunning and cease from exhibiting the wiles that befit Ulysses, the rest of the suitors could move on to marry other women within the city-state.

While we, awaiting this, all our days

quarrel for the sake of her excellence, nor ever go after

others, whom anyone of us might properly marry.

(2.205-7)

While Homer provides a one-sided narrative, the comments of the suitors and the actions of Telemachus portray a different alternative scenario. The mentor of Ulysses intercedes to state that the Ithacan people are to blame for the excesses of the suitors. “I hold it against you other people, how you all sit there in silence, and never with an assault of words try to check the suitors, though they are so few, and you so many”.[53] This reproach given by the mentor of Ulysses to the Ithacan people makes it clear that they are acting cowardly.

The suitors argue that they do not wish to consume the estate of Telemachus, for it is damaging themselves. Moreover, it is not Penelope’s estate rather belongs to Telemachus if Ulysses is truly deceased. Given the decade that he has been away at war, this must surely be the case, and they argue that the wooing should come to a decision. The continuous courting of an elderly coquette would seem out of place if the estate is truly to go to Telemachus. In this, it is clear that it is not the appeal and attractiveness of Penelope that has enticed the suitors. Rather, the suitors would more likely be seeking the right to kingship through marriage ties.

The Ithacan monarchy was not hereditary. As a result, Telemachus as a teenager does not seem to manage his household and becomes unlikely to form the political support necessary to become King if his father is dead. In addition, the primary suitor, Antonis, would appear not to want to marry Penelope. Rather, Antonis seems likely to be willing even to murder Telemachus if this will further his ambitions. The other suitors have ambitions that are less clear. The differences in the goals of the suitors do not matter to Ulysses. Ulysses merely sees a suitor as a suitor, and they are painted the same way.

The result is that Ulysses murders all the suitors save for the minstrel in the Herald. These individuals are tasked with singing his glory. Conversely, we can imagine a series of stories in a modern form where unwanted guests come to stay. Even Tolkien’s story The Hobbit starts with unwanted guests eating Bilbo Baggins out of house and home. Yet, we could hardly imagine Bilbo Baggins going on a rampage and killing all of the dwarves. Nor could we imagine writing stories and songs about such a killing spree.

To the victor goes the spoils, and as the strongest warrior, Ulysses assumes the right to determine history. In this, Penelope is pure and white. The suitors are flawed and tragic but deserving of the end. In modern stories, it is common for the hero to be flawed and even question the actions taken. Yet, such a path would merely be seen as a weakness for those in classical Greece. Consequently, in analysing Homer’s work, we can see significant cultural differences between our societies and use this as a mirror to reflect on changes.

Deus Ex Machina

The Odyssey is full of digressions and flashbacks. Erich Auerbach juxtaposed biblical and Homeric narratives, noting that stories such as Genesis are formed in a bareness of narration. Conversely, Homer creates a story bursting at the seams with incidental details. We may also see a different vision of the world in these two ways of telling a story. In Genesis, God intervenes but only indirectly. But in Homer’s tail, the gods intervene steadily. Neptune constantly sends storms and bad weather to increase the distress faced by Ulysses.

Minerva assumes human form and brings Ulysses good fortune. Throughout the story, nymphs, enchantresses and all manner of the divine aid or hinder Ulysses to fulfil their own ends. To Homer, the supernatural intervention of competing beings acting both to help and hinder humanity forms a constant backdrop to the story. So, despite the wiles and sagacity of Ulysses, it is always the gods who intervene when all seems too difficult. This epic tale brings Ulysses through a series of extraordinary accomplishments, yet it is not through his own volition.

Primitive tribal integration of the supernatural is an essential aspect of the character’s survival for Homer.[54] It is not for humanity to decide the protagonist’s fate but rather the gods’ decision. To a modern sensibility, the necessity to consistently introduce divine interference seems like the God from the machine. Rather than allowing the character to develop and experience choice and free will, the gods and fate decide our destiny.

Conclusion

Ulysses presents a very different character compared to the romantic era hero. He is all too human. He is flawed and marked by typical human problems. His pride is in excess at times, and causes problems for himself and others around him. Yet, despite the cultural differences that are bound to appear throughout the epic, the flawed humanity of Ulysses leaves a hero that, even today, can be understood. We see an individual who can exhibit traits of magnanimity, mercy, and tender-heartedness yet, equally, act in a way that fails to belie the coldhearted inhuman and pitiless actions that are occasionally taken.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Cf. Ovid, Metamorphoses, I, 78ff.

Gen. 18:23, 25.

Odyssea.

Secondary Sources

Applebaum, Herbert A, The Concept of Work : Ancient, Medieval, and Modern. (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992)

Butler, Samuel (trans.), and Homer, The Iliad of Homer and The Odyssey: Britannica Great Books Encyclopedic Edtion (University of Chicago, 1952)

Clarke, Howard W., ‘Telemachus and the Telemacheia’, The American Journal of Philology, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 84.2 (1963), 18

Cohen, Anthony P., Symbolic Construction of Community, 0 edn (Routledge, 2013) <https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203131688>

Cooppan, Vilashini, ‘World Literature and Global Theory: Comparative Literature for the New Millennium’, Symplokē, 9.1/2 (2001), 15–43 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/40550499> [accessed 5 March 2022]

Daly, Pierrette, Heroic Tropes: Gender and Intertext (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1993)

Danilova, Nataliya, and Ekaterina Kolpinskaya, ‘The Politics of Heroes through the Prism of Popular Heroism’, British Politics, 15.2 (2020), 178–200 <https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-019-00105-8>

Dilworth, Thomas, ‘The Fall of Troy and the Slaughter of the Suitors: Ultimate Symbolic Correspondence in the “Odyssey”’, 2022, 25

Doherty, Lillian Eileen, Siren Songs: Gender, Audiences, and Narrators in the Odyssey (University of Michigan Press, 1995)

Edmundson, Mark, Literature against Philosophy, Plato to Derrida: A Defence of Poetry (Cambridge University Press, 1995)

Farenga, Vincent, Citizen and Self in Ancient Greece: Individuals Performing Justice and the Law (Cambridge University Press, 2006)

Ford, Andrew Laughlin, Homer: The Poetry of the Past (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019)

Friedman, Susan Stanford, ‘Weaver and Artist: Surveying a Penelope’, A Penelopean Poetics: Reweaving the Feminine in Homer’s Odyssey, 2004, 83

Gifford, Don, and Robert J. Seidman, Ulysses Annotated: Notes for James Joyce’s Ulysses (Univ of California Press, 1988)

Gloyn, Liz, Tracking Classical Monsters in Popular Culture (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019)

Gregory, Elizabeth, ‘Unravelling Penelope: The Construction of the Faithful Wife in Homer’s Heroines’, Helios, 23.1 (1996), 3–20

Haft, Adele J., ‘“The City-Sacker Odysseus” in Iliad 2 and 10’, Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-), 120 (1990), 37 <https://doi.org/10.2307/283977>

Hall, Edith, Introducing the Ancient Greeks (London: Bodley Head, 2015)

———, ‘The Return of Ulysses: A Cultural History of Homer’s Odyssey’, 2008

Heitman, Richard, Taking Her Seriously: Penelope & the Plot of Homer’s Odyssey (University of Michigan Press, 2005)

Helms, Mary W., Ulysses’ Sail (Princeton University Press, 2014)

Jameson, Michael H., ‘Agriculture and Slavery in Classical Athens’, The Classical Journal, 73.2 (1978), 25

Kardulias, Dianna Rhyan, ‘Odysseus in Ino’s Veil: Feminine Headdress and the Hero in Odyssey 5’, Transactions of the American Philological Association, 131.1 (2001), 23–51 <https://doi.org/10.1353/apa.2001.0011>

Kirk, Geoffrey Stephen, Myth: Its Meaning and Functions in Ancient and Other Cultures (Univ of California Press, 1973)

Koene, Casper J., ‘Tests and Professional Ethics and Values in European Psychologists’, European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 13.3 (1997), 219–28 <https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.13.3.219>

Louden, Bruce, ‘Is There Early Recognition between Penelope and Odysseus?; Book 19 in the Larger Context of the” Odyssey”’, College Literature, 2011, 76–100

McCartney, Eugene S., ‘Maeonides and Poverty: An Annotation’, The Classical Journal, 48.1 (1952), 30–33

Murgatroyd, Paul, The Wanderings of Odysseus, 2021

Myrsiades, Kostas, ‘Reading Homer’s Odyssey’, 2021

Patterson, Cynthia, The Family in Greek History (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1998)

Prickett, Stephen, Origins of Narrative: The Romantic Appropriation of the Bible (Cambridge [England] ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996)

Richardson, Scott, ‘The Devious Narrator of the” Odyssey”’, The Classical Journal, 2006, 337–59

Rivkin, Julie, and Michael Ryan, eds., Literary Theory: An Anthology, Third Edition (Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell, 2017)

Trahman, C. R., ‘Odysseus’ Lies (“Odyssey”, Books 13-19)’, Phoenix, 6.2 (1952), 31 <https://doi.org/10.2307/1086270>

Verhelst, Berenice, ‘Six Faces of Odysseus: Genre and Characterization Strategies in Four Late Antique Greek “Epyllia”’, Symbolae Osloenses, 93.1 (2019), 132–56 <https://doi.org/10.1080/00397679.2019.1648018>

Webster, T. B. L., Athenian Culture and Society (University of California Press, 1973) <https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520316522>

Welsh, Alexander, Hamlet in His Modern Guises (Princeton University Press, 2001) <https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400824120>

Whitman, Cedric H., Homer and the Heroic Tradition: (Harvard University Press, 1958) <https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674862845>

Wimsatt, James I., ‘12. The Idea of a Cycle: Malory, the Lancelot-Grail, and the Prose Tristan’, in The Lancelot-Grail Cycle, ed. by William W. Kibler (University of Texas Press, 1994), pp. 206–18 <https://doi.org/10.7560/743175-013>

[1] Samuel (trans.) Butler and Homer, The Iliad of Homer and The Odyssey: Britannica Great Books Encyclopedic Edtion (University of Chicago, 1952).

[2] Liz Gloyn, Tracking Classical Monsters in Popular Culture (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019).

[3] Mary W. Helms, Ulysses’ Sail (Princeton University Press, 2014); Edith Hall, ‘The Return of Ulysses: A Cultural History of Homer’s Odyssey’, 2008, p. 138.

[4] Lillian Eileen Doherty, Siren Songs: Gender, Audiences, and Narrators in the Odyssey (University of Michigan Press, 1995), p. 24.

[5] Vincent Farenga, Citizen and Self in Ancient Greece: Individuals Performing Justice and the Law (Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 84.

[6] C. R. Trahman, ‘Odysseus’ Lies (“Odyssey”, Books 13-19)’, Phoenix, 6.2 (1952), 31 <https://doi.org/10.2307/1086270>.

[7] Elizabeth Gregory, ‘Unravelling Penelope: The Construction of the Faithful Wife in Homer’s Heroines’, Helios, 23.1 (1996), 3–20; Bruce Louden, ‘Is There Early Recognition between Penelope and Odysseus?; Book 19 in the Larger Context of the" Odyssey"’, College Literature, 2011, 76–100.

[8] Casper J. Koene, ‘Tests and Professional Ethics and Values in European Psychologists’, European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 13.3 (1997), 219–28 <https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.13.3.219>.

[9] Butler and Homer; Susan Stanford Friedman, ‘Weaver and Artist: Surveying a Penelope’, A Penelopean Poetics: Reweaving the Feminine in Homer’s Odyssey, 2004, 83.

[10] Scott Richardson, ‘The Devious Narrator of the" Odyssey"’, The Classical Journal, 2006, 337–59.

[11] Vilashini Cooppan, ‘World Literature and Global Theory: Comparative Literature for the New Millennium’, Symplokē, 9.1/2 (2001), 15–43 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/40550499> [accessed 5 March 2022]; Literary Theory: An Anthology, ed. by Julie Rivkin and Michael Ryan, Third edition (Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell, 2017).

[12] Don Gifford and Robert J. Seidman, Ulysses Annotated: Notes for James Joyce’s Ulysses (Univ of California Press, 1988).

[13] Pierrette Daly, Heroic Tropes: Gender and Intertext (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1993).

[14] Andrew Laughlin Ford, Homer: The Poetry of the Past (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019).

[15] Eugene S. McCartney, ‘Maeonides and Poverty: An Annotation’, The Classical Journal, 48.1 (1952), 30–33 (p. 30).

[16] Cedric H. Whitman, Homer and the Heroic Tradition: (Harvard University Press, 1958) <https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674862845>.

[17] Stephen Prickett, Origins of Narrative: The Romantic Appropriation of the Bible (Cambridge [England] ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

[18] Mark Edmundson, Literature against Philosophy, Plato to Derrida: A Defence of Poetry (Cambridge University Press, 1995), p. 10.

[19] Cynthia Patterson, The Family in Greek History (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1998), p. 16.

[20] Michael H. Jameson, ‘Agriculture and Slavery in Classical Athens’, The Classical Journal, 73.2 (1978), 25; Herbert A Applebaum, The Concept of Work : Ancient, Medieval, and Modern. (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992).

[21] Anthony P. Cohen, Symbolic Construction of Community, 0 edn (Routledge, 2013), p. 14 <https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203131688>. This is described by Anthony as the “arcane fantasy of myth and totem”.

[22] Edith Hall, Introducing the Ancient Greeks (London: Bodley Head, 2015), pp. 39, 245.

[23] T. B. L. Webster, Athenian Culture and Society (University of California Press, 1973) <https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520316522>.

[24] Whitman, p. 24.

[25] Butler and Homer, pp. 201-2,227, 248.

[26] Od. 8.75-82; 8.499-500.

[27] Adele J. Haft, ‘“The City-Sacker Odysseus” in Iliad 2 and 10’, Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-), 120 (1990), 37 (p. 37) <https://doi.org/10.2307/283977>.

[28] Thomas Dilworth, ‘The Fall of Troy and the Slaughter of the Suitors: Ultimate Symbolic Correspondence in the “Odyssey”’, 2022, 25 (p. 14).

[29] Kostas Myrsiades, ‘Reading Homer’s Odyssey’, 2021.

[30] Myrsiades.

[31] Nataliya Danilova and Ekaterina Kolpinskaya, ‘The Politics of Heroes through the Prism of Popular Heroism’, British Politics, 15.2 (2020), 178–200 <https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-019-00105-8>.

[32] Hall, ‘The Return of Ulysses: A Cultural History of Homer’s Odyssey’, pp. 40–41.

[33] James I. Wimsatt, ‘12. The Idea of a Cycle: Malory, the Lancelot-Grail, and the Prose Tristan’, in The Lancelot-Grail Cycle, ed. by William W. Kibler (University of Texas Press, 1994), pp. 206–18 <https://doi.org/10.7560/743175-013>.

[34] Berenice Verhelst, ‘Six Faces of Odysseus: Genre and Characterization Strategies in Four Late Antique Greek “Epyllia”’, Symbolae Osloenses, 93.1 (2019), 132–56 <https://doi.org/10.1080/00397679.2019.1648018>.

[35] Dianna Rhyan Kardulias, ‘Odysseus in Ino’s Veil: Feminine Headdress and the Hero in Odyssey 5’, Transactions of the American Philological Association, 131.1 (2001), 23–51 <https://doi.org/10.1353/apa.2001.0011>.

[36] Kardulias.

[37] Butler and Homer, p. 258.

[38] Paul Murgatroyd, The Wanderings of Odysseus, 2021.

[39] Butler and Homer, p. 251.

[40] Butler and Homer, p. 239.

[41] Butler and Homer, p. 273.

[42] Murgatroyd, pp. 55, 172.

[43] Howard W. Clarke, ‘Telemachus and the Telemacheia’, The American Journal of Philology, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 84.2 (1963), 18.

[44] Alexander Welsh, Hamlet in His Modern Guises (Princeton University Press, 2001) <https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400824120>.

[45] Butler and Homer, p. 185.

[46] Butler and Homer, p. 187.

[47] Butler and Homer, p. 185.

[48] Butler and Homer, p. 273.

[49] Welsh.

[50] Butler and Homer, p. 302.

[51] Richard Heitman, Taking Her Seriously: Penelope & the Plot of Homer’s Odyssey (University of Michigan Press, 2005), pp. 26–27.

[52] Od. 2.187-82.

[53] Od. 2.187-91.

[54] Geoffrey Stephen Kirk, Myth: Its Meaning and Functions in Ancient and Other Cultures (Univ of California Press, 1973), pp. 20, 193.

[Image source: Eleusis Amphora: funerary proto-Attic amphora. Detail of the neck: Odysseus and his men blinding the cyclops Polyphemus., Napoleon Vier, CC BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/, Wikimedia Commons]