Edgeworth set Castle Rackrent in a period where the Irish were under English rule. Unfortunately, most English people failed to understand the underlying tensions within Irish politics during the eighteenth century (Garvin). The grammar used by Edgeworth and the local terminologies deployed within her work capture some of the disparities in grammar and language that had been used, in part, as a cultural battlefield (Mitchell) by the English aristocracy in the oppression of the Irish. Castle Rackrent (Edgeworth) uses non-standardised grammar. As Mitchell noted, grammar was utilised by the English to mark social groups, and the standardisation of English grammar being taught within schools differentiated marginal groups and provided a means to distinguish social groups such as those with an Anglican origin from those of Irish descent.

The eighteenth century marked one of the most critical times in the development of the English Empire (Rule). During this time, the birth of the Industrial Revolution and the creation of new forms of finance and domestic and overseas markets led to the development of a modern economy and the growth of England as a world power. In addition, the English Georgian economy saw the American colonies break from British rule. At this time of the Union, the Irish had no poor law (Mullaney) but had been constrained to maintain the Irish island as part of the Union.

Additionally, many aspects of the standardised grammar being formed aligned with the liturgy of the English Anglican church (Rivers). The Irish population at the time was strongly divided between the disenfranchised Catholic peoples, subject to English rule, and the Anglican English and Irish, who maintained the voting franchise and rights. In her work, Edgeworth presents a story based on those of her own family history. This account was obtained from The Black Book of Edgeworthstown, representing many individuals who had expressed attitudes similar to those of the characters in the Edgeworth short story.

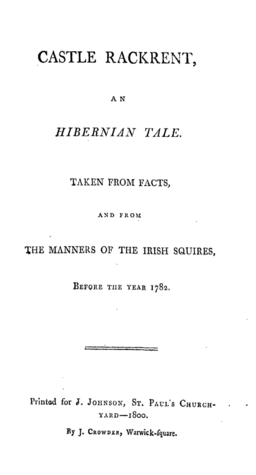

The book incorporates an introduction, a glossary, and footnotes, which have been written in the expression of an English narrator, highlighting the distinction between the English and Irish forms of speech. Edgeworth tells the story as it is seen through Thady Quirk's perspective and an anonymous editor's comments. The footnotes and glossary are offered "for the information of the ignorant English reader."

The story documents the history of three generations of the Irish Rackrent family, told through the eyes of a servant to the family. The novel progresses as a monologue, documenting the drinking habits of a member of the English gentry and ruling class in Ireland. Edgeworth speaks to the audience, and doesn’t involve them, in a manner reminiscent of Waiting for Godot (Beckett). As with this post-modern play, Edgeworth has the reader waiting for something to happen or a plot to form when nothing occurs.

Even the novel fails to end, hence the allegory presented within Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (Fitzgerald). Here, Gatsby alludes to the end of the novel by pointing out the end of Castle Rackrent. As the head of the household passes away, the estate is divided between creditors, leaving an empty void and opening to the story. Similarly, Gatsby finishes along the lines of a character heading an empty drunken Empire with no continuation. The collapse is captured through the actions of a trusted party who betrayed the main character. In both stories, the estate's fate was written in the early actions of the individuals manipulating the outcomes.

The Rackrent family and all who parasitically live off them attempt a Gatsby-like experience by drinking, eating, and wanting to party too much, and the outcome is the dissolution of the estate. Yet, in telling the story to the English, Edgeworth is not painting a portrait of drunken poor Irishmen, but one of empty English gentry with no real purpose or understanding of the country they live in. As the active Union was approaching, Edgeworth captured the spirit of Irish rebellion by portraying the English gentry in a highly negative light.

While the story maintains very little plot, jumping randomly in a Markov walk person-to-person and from place to place, it stumbles aimlessly through the drunken English gentry as they come and go from the estate. As each character stumbles into and out of the story, Edgeworth has them walking in a bibulous stupor, not seeing the end of their own society. As characters return from Bath and other areas of England, they have racked up debt from gambling and extended aristocratic parties.

There is an underlying morality tale and story. The decline of a noble Irish house pushed into penury occurs through a lack of stewardship and the use of the rack-rent policy of forming tiered rental structures, where those making a living on the land had no incentive to improve the quality of their tenure. The combination of extravagant living, throwing money at legal cases, and losing nearly all of them is coupled with the distorted view of a loyal retainer who fails to understand the changes happening to society.

Thady Quirk maintains a twisted form of loyalty that allows him to interpret and report on the family's behaviour in a manner that presents it commendably, with all of the accesses helping to explain the aristocratic grandeur of the house. The more miserly and controlled attitudes of the new gentry who made money through commerce are compared as penny-pinching and beyond the noble nature of the current household. In part, the disdain for this new gentry may be attributable to the fact that they are less manipulable.

The work presents many interesting historical quirks of Irish society. Notably, the practise of locking up wives to have them hand over their valuables was not well known in England. In addition, the process of running for Parliament and being elected as a parliamentarian was commonly deployed to escape debt. Yet, Thady Quirk manages to cover up all of the family faults, including the processes of purloining the property of wives and the process of escaping debt.

The story captures and presents some of the racial contrasts of the time. The head of the household marries a Jewish wife with the justification that he will use her money to retain part of the estate. Yet, the plot or plan fails when it turns out that the new wife is not rich. Here, the prejudicial stereotype of all Jews having money is presented within the story. The story captures some of the inequities faced by women and the complex relationships between the Irish and the Jews. As with Sense and Sensibility (Austen), the lack of property rights and the method of how fathers or husbands would control inheritances and estates owned by women are presented in an analogous perspective.

Thady Quirk gives an unreliable narration. The mode of address presented by Edgeworth is best noted as one by an Irish retainer seeking to make his own position grander. Despite the failed cases, Thady presents the family as aristocratic and beyond reproach.

"I knew how it was; Sir Murtagh was a great lawyer, and looked to the great Skinflint estate; there, however, he overshot himself; for though one of the co-heiresses, he was never the better for her, for she outlived him many’s the long day – he could not see that to be sure when he married her. I must say for her, she made him the best of wives, being a very notable, stirring woman, and looking close to everything. But I always suspected she had Scotch blood in her veins; anything else I could have looked over in her from a regard to the family." (Edgeworth).

Edgeworth selected a minor character as the unreliable narrator. In structuring a compromised viewpoint, Edgeworth creates an unreliable filter for the story. As an unreliable narration, the story being told cannot be fully trusted. Thady Quirk is just as likely to be strung out on alcohol or engaged in petty larceny as any other character. The difficulty is derived from the commonality of all unreliable narrators; they are deceptive (Mete). As a result, Edgeworth introduces a suitable allowance of uncertainty, and provides an opportunity for English readers to discount anything that offends them as the rantings of a drunken servant.

The book's first section starts with a short history of the family. At this point, the narrator seems to be trustworthy. Yet, as the story progresses, certain descriptions start to seem more implausible, and the dichotomy between the embellished view of the family and the mounting levels of creditors and failing cases makes the reader wonder whether the retainer has any understanding of what is really occurring or even whether the entire framework of the story is being embellished.

While Edgeworth starts presenting the story of the Rackrent family in a historically grounded manner, Thady Quirk becomes obvious and simultaneously confusing. In some ways, the narrator is presented as an outsider. Thady Quirk is prejudiced by class and culture as a retainer outside of the gentry looking in. The version of events presented in the story is skewed based on the attitude of a family retainer who has a vested interest in promoting the family. By covering up the family's faults, Thady Quirk reports to be loyal, but equally, he betrays and sometimes belittles them.

"Honest" Thady Quirk (Edgeworth 7) outlives generations of the family and reports to be writing the memoirs of the household “out of friendship for the family”. Yet, Thady spends more time gossiping in a format that would be better situated around the water cooler than as a historical memoir. In documenting the story, Sir Connolly Thady presents a story of gross negligence and an abject failure to manage the estate. An editor of Thady’s memoirs (the author of the book) presents a glossary of Irish terms “for the information of the ignorant English reader” (Edgeworth 4), managing to simultaneously poke fun at the English reader.

The narrator shows his obvious bias towards those he could likely manipulate for money. When Sir Murtagh’s brother, Sir Kit, and Harrison take over management of the estate, Thady reminiscences how the young master carelessly gives him a guinea with an attitude that “money to him was no more than dirt” (Edgeworth 20). Yet, Jason, Thady’s son, is working with the middlemen, both learning the business of such individuals and copying the accounts. So when part of the estate is put up for forced sale, Jason can bid for it.

Jason takes over the property from Sir Kits at a bargain basement price. Yet, it becomes difficult to trust the narrator's loyalty with the narrator's son actively engaged in deception. Then, during the conversations with the people sent to arrest Sir Condy for debt, Jason is noted to be the agent of the Rackrent estate and manages to buy up all the debts held against Sir Condy. This allows him to enforce the debts and simultaneously use such subterfuge to buy up the estate at an undervalued price.

While Thady decries how he is “grieved and sick at heart for my poor master” (Edgeworth 77), he does not even talk to his own son and stop him from deceiving and taking the estate of his master. Moreover, even from the start, the mantle was described as “a fit house for an outlaw, a meet bed for a rebel, and an apt cloak for a thief” (Edgeworth 8). The story presented by Edgeworth captures a duplicitous servant who was equally a colonised subject feigning loyalty while undermining their rule. The subversion of the Rackrent family is prolonged and exaggerated. Through the continuing deception and feigned loyalty, Thady allows his son to slowly bleed the wealth out of the family. In part, the lack of financial management and stewardship destroys the family, but the process is equally accelerated through trusted servants' assistance.

References

Austen, Jane. Sense and Sensibility. Cassell, 1908.

Beckett, Samuel. Waiting for Godot: A Tragicomedy in Two Acts. Grove Atlantic, 2011.

Edgeworth, Maria. Castle Rackrent. OUP Oxford, 2008.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby. 1st Collier Books ed, Collier Books; Maxwell Macmillan Canada; Maxwell Macmillan International, 1992.

Garvin, Tom. The Evolution of Irish Nationalist Politics: Irish Parties and Irish Politics from the 18th Century to Modern Times. Gill & Macmillan Ltd, 2005.

Mete, Barış. The Unreliable Narrator and the Problem of Deceptive Narration. Deception: Spies, Lies and Forgeries, Brill, 2016, pp. 19–28.

Mitchell, Linda C. Grammar Wars: Language as Cultural Battlefield in 17th and 18th Century England. Routledge, 2019. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315209845

Mullaney, Susan. A Means of Restoring the Health and Preserving the Lives of His Majesty’s Subjects: Ireland’s 18th-Century National Hospital System. Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, vol. 29, no. 2, Oct. 2012, pp. 223–42. utpjournals.press (Atypon), https://doi.org/10.3138/cbmh.29.2.223

Rivers, Isabel. Books and Their Readers in 18th Century England: Volume 2 New Essays. A&C Black, 2003.

Rule, John. The Vital Century: England’s Economy 1714-1815. Routledge, 2014, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315836386