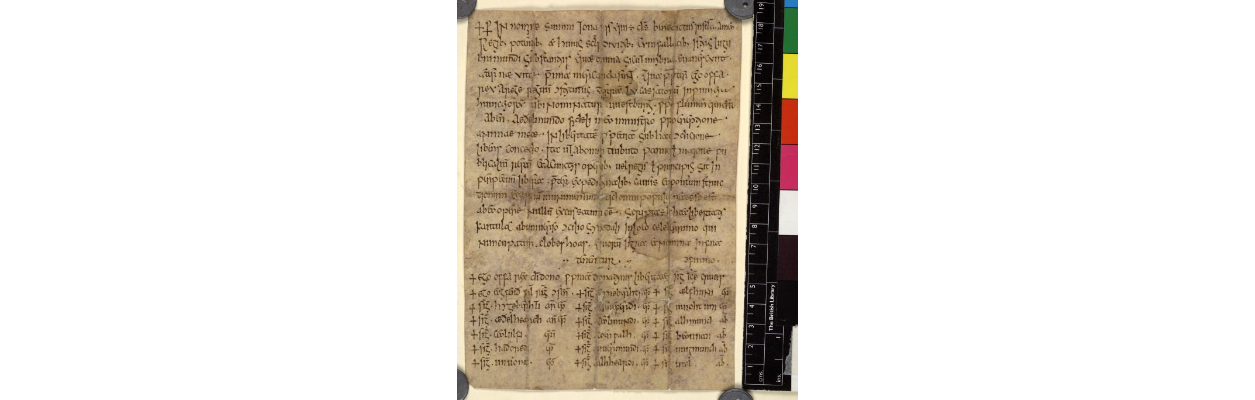

British Library, Add Charter 19790:

http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=add_ch_19790_f001r

P.H. Sawyer, Anglo-Saxon Charters: An Annotated List and Bibliography, Royal Historical Society Guides and Handbooks, 8 (London: Royal Historical Society, 1968), no. 139.

Commentary

In this late eighth-century document, King Offa of Mercia provides a grant of land to an official, Æthelmund, father of Æthelric, and his family.[1] The terms of the document issue an estate of fifty-five hides (manentes, cassati, or hides) in Westbury near the river Avon.[2] The document is believed to be dated between 793 and 796, which would be the final year possible as King Offa died that year. Fifty-five hides would be considered very large.[3] As Warren Hollister notes, a five-hide unit would extend to an obligation of eleven men to the fyrd. The land grant would span multiple counties. An example of such size would be reflected in an estate of forty hides granted under S1171 to a minister in Barking, that is known to span 60 mi².

Hollister notes that a general agreement existed concerning the matter of the five-hide unit.[4] Every five-hide group pre-conquest England “owed one warrior to the fyrd”.[5] Nevertheless, many varieties of the bargain are noted to be derived, and the customs of the shire are more important than the later concepts around the size of a hide. The fyrd was a form of an Anglo-Saxon military unit created through the mobilisation of freedmen or mercenaries who would be required to defend the estate they were obligated to. Although noted to be of short duration, the men at arms would have been expected to provide their weapons, armour, and provisions. Based on the landholding assessed in the hide, the individual Lord was required to contribute men and arms and defend the burhs. Primarily, the fyrd consisted of the more hardened soldiers, supplemented by the addition of ordinary villages and the peasantry, who would be expected to escort their Lord.

Gallagher and the Wiles note that early Anglo-Saxon charters are generally specimens that exist through the copying in later chronicles, cartularies, and other contexts.[6] There are concerns around the document concerning the diploma. Both S 146 and S 139 contain indications that could have been copied, and several authors have noted it could have been changed.[7] Baxter argues that when Wulstan became Bishop of Worcester in 1002, many charters relating to the endowment of the church of Worchester were copied into a cartulary. As Baxter notes, the Worchester community reinvented various aspects of its Anglo-Saxon past.[8] Yet, the proem and the nature of the dorse make it likely that the document is genuine.[9] The single scribe of the Charter has continued across the dorse. The witness list to the diploma King Offa begins on the face and continues with little attention paid to the visual presentation on the back of the sheet.[10]

Tini demonstrates that the wealth of information contained within the Worcester archive provides a wealth of evidentiary material.[11] Of particular note, the church of Worcester has preserved two 11th-century cartularies, which provide the earliest accident collection of its type. It also needs to be noted that the modality of preservation provides insight into how the eleventh-century cathedral church acted through successive restructuring and how the earlier title deeds were used as a basis for continuing development. Tini explores the reuse of documents and the methodologies of how the documents were copied.[12] Moreover, the inconsistencies between the documents and the work of palaeographers and diplomatists add weight to such documents, despite the large numbers of forged or spurious documents from religious houses in Western Europe.[13]

This information and the investigations and testing by other researchers suggest that S139 is genuine and contemporary with the grant.[14] The document is known to survivors as a single-sheet original, with a copy held in Worcester’s early 11th-century cartulary, Liber Wigorniensis. King Offa issued the document during a synod that is noted to be held at Clofesho. The dating of between 793-6 was established by analysing the witnesses present, and it is believed that the synod occurred in 794.[15] Details of the copy are available and discussed by Stephen Baxter in more detail.[16]

It has been noted that there are other documents, such as charter S146, preserved in the Liber Wigorniensis that make no mention of Æthelmund or his descendants. Yet, since the grant of sixty hides at Westbury and twenty near Henbury exhibit a large grant of land, the lack of reference to another service should not cause concern. Scholarship and documents surround the creation of the Council recorded as the third Council of Clovesho in 794. In this Council, a new archbishopric was created at Lichfield, and the Mercian Sees were to be subjected to that jurisdiction withdrawn from Canterbury. At this Council that is noted that the Archbishop of Lichfield signed as an archbishop. This Council supposedly was held somewhere near London in Mercia.[17]

The reference to God as the supreme thundering being would imply an overlap between Christianity and the remaining Norse gods. The use of terminology to say how money is deceitful indicates the religious tone of the time. The grant of fifty-five hides of land is made in Westbury near the river Avon. As noted above, the grant removes all tribute to the state other than that required through military service and feudal fiefdoms. It further requires the maintenance of trade routes such as bridges and those required to maintain defences. It is noted that no individual should be free of that obligation. The witnesses of the Charter are noted to be the entire Council of the Synod.[18] These rights and obligations are an important aspect of the Charter as the Lord that neglects military service may be required to pay 120 shillings and forfeit his land under the law of Ine.[19]

The signatories are done under the grant of the side of the holy cross. This is a form known as Signa and differs from the methodology used from the Norman conquest. The individual places a cross against the name before the witnesses, representing that they agree to be bound under oath to God.

Translation

Grant from Offa, King of Mercian peoples to Æthelmund of land in Westbury in the province of huuicciorum.

In the name of the supreme thunderer, who is God blessed forever, amen. By potent kings and the rich men of this world, the rewards of eternal life must be purchased with the deceitful things of this mournful world, which all vanish like a shadow. For this reason, I, Offa, named king by the king of kings, for the rescue of my soul freely grant to Aethelmund, my faithful minister, fifty-five hides of land in the province of the Wiccas, in the place that is named Westbury, near the river that is called Aben, in perpetual freedom, on this condition, that it may be forever free from all tribute to the state, small or greater, and from all services, whether to king or prince, except military service and the making of bridges and the maintenance of defences, because it is necessary for all people that none should be excused from this obligation. The entire synodal council wrote this chart of livery in that very famous place that is called Clobeshoas, whose signs and names are preserved below:

Previous Translation:

In the name of the supreme thundering being who is God blessed forever amen. Through the actions of potent regions and the wealthy men of this earth the rewards of eternal life unnecessarily purchased with the deceitful things of this sorrowful world, all of which vanish in a shade.

As such, I, Offa, ascended to be King by the King of kings in order to rescue my soul freely grant to Æthelmund as my devoted servant fifty-five manentes of workable land in the province of the Huuicciori in the place which is named Westbury near the river that is called Avon in eternal liberty under the condition that it shall be forever free from all tribute to the state, small or greater and from all services, whether to the sovereign or Doyen except military service and the making of bridges and the maintenance of defences due to the necessity of all of the people that none should be excused from this obligation and duty.

This charter of regalia was drafted by the complete Council of the Synod in the famed location called Clobeshoas, with the names of the signatories and their sign to God preserved below:

+ I, Offa, by God’s gift and King confirm my own insignia of the grant with the sign of the holy cross.

+ I ecgfer, the son of the king do hereby agree

+ I, Archbishop Hygeberht

Etc.

There are multiple names over the two pages ranging from senior to a less senior position starting with the King, going to bishops, going to presbyters and then people without rank or title that are listed. See the end of this paper for a list.

Document in Latin

In nominee summi tonantis qui est deus Benedictus in secula amen. Regibus potentibus et humius seculi divitibus cum fallacibus istius lugubri mundi substantiis quae omnia sicut umbra eunanescunt aeternae vitae promia mercanda sunt.

Quapropter ego Offa Rex a rege reguum constitutes terram l.v. Cassatorum in provincial huuicciorum ubi nominator uuestburg prope flumen qui dictur aben Æthelmundo fideli meo ministro pro ereptione animae meae in libertatem perpetuam sub hac condicione libens concede ita ut ab omni tribute paruo vel maiore publicalium rerum et a cunctis operibus uel regis uel principis sit in perpetuum libra preter expeditionalibus causis et pontum structionum et arcium munimentum quid omni populo necesse et ab eo opera nullum excssatum esse. Scripta est autem haec liberatatis kartula ab universio concilio synosali in loco celeberrimo qui nuncupatur clobeshoas.

Quorum signa et nmina infra tenentur.

+ Ego Offa rex deid ono proprian donationis libertatem signo sancta crucis confirmio

+ Ego ecgfer filius regis consensi

+ Signum hygeberhti archiepiscopi

Etc…

References

Attenborough, Frederick Levi, ed. The laws of the earliest English kings. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 2006.

BEDE, Historia Eccl. Gentis Anglorum, ed. Plummer (Oxford, 1896).

Bates, David, “The Prosopographical Study of Anglo-Norman Royal Charters: Some Problems and Perspectives”, In Family Trees and the Roots of Politics: The Prosopography of Britain and France from the Tenth to the Twelfth Century, ed. K. S. B. Keats-Rohan. Woodbridge, 1997.

Baxter, Stephen. “Archbishop Wulfstan and the Administration of God’s property.” In Wulfstan, Archbishop of York: the proceedings of the second Alcuin conference, pp. 161-205. 2004.

Bevan, Kitrina Lindsay. “Clerks and scriveners: Legal literacy and access to justice in late Medieval England.” (2013).

Burn, Edward Hector, and John Cartwright. Cheshire and Burn’s Modern Law of Real Property. Oxford University Press, USA, 2011.

Caliendo, Kevin A. Diplomatic Solutions: Land Use in Anglo-Saxon Worcestershire. Diss. Loyola University Chicago, 2014.

Cubitt, Catherine. Anglo-Saxon church councils c. 650-c. 850. Leicester University Press, 1995.

Dutton, Marsha. A Companion to Aelred of Rievaulx (1110–1167). Brill, 2016.

Gallagher, Robert, and Kate Wiles. “The Endorsement Practices of Early Medieval England.” The Languages of Early Medieval Charters. Brill, 2020. 230-295.

Gurney, Daniel. The record of the house of Gournay.[With]. Vol. 2. 1848. https://archive.org/details/recordhousegour01gurngoog/page/n3/mode/2up

Haskins, George L. “The Development of Common Law Dower.” Harv. L. Rev. 62 (1948): 42.

Hollister, C. Warren. “The Five-Hide Unit and the Old English Military Obligation.” Speculum 36, no. 1 (1961): 61-74. Accessed March 30, 2021. doi:10.2307/2849844.

Jaspert, Nikolas, and Karl Borchardt. “Scribes and Notaries in Twelfth-and Thirteenth-Century Hospitaller Charters from England.” The Hospitallers, the Mediterranean and Europe. Routledge, 2016. 197-208.

Kaye, John Marsh. Medieval English Conveyances. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Keats-Rohan, K. S. B., and David E. Thornton. “COEL and the Computer: Towards a Prosopographical Key to Anglo-norman Documents, 1066-1166.” Medieval Prosopography 17, no. 1 (1996): 223-62. Accessed March 30, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44946219.

Macleod, Henry Dunning. “Coinage of Britain”. A Dictionary of Political Economy. 1. London: Longman, Brown, Longmans and Roberts (1863). p. 459.

Morley, Claude. 1923. “Clovesho - The Councils And The Locality”. Suffolkinstitute.Pdfsrv.Co.Uk. http://suffolkinstitute.pdfsrv.co.uk/customers/Suffolk%20Institute/2014/01/10/Volume%20XVIII%20Part%202%20(1923)_Clovesho%20-%20the%20councils%20and%20the%20locality%20Claude%20Morley_91%20to%20106.pdf.

Pons-Sanz, Sara M. “Aldred’s Glosses to the notae iuris in Durham A. iv. 19: Personal, Textual and Cultural Contexts.” English Studies 102.1 (2021): 1-29.

Power, Daniel. “The Transformation of Norman Charters in the Twelfth Century.” In People, Texts and Artefacts: Cultural Transmission in the Medieval Norman Worlds, edited by Bates David, D’Angelo Edoardo, and Van Houts Elisabeth, 193-212. London: University of London Press, 2017. Accessed March 30, 2021. doi:10.2307/j.ctv512xnf.17.

P.H. Sawyer, Anglo-Saxon Charters: An Annotated List and Bibliography, Royal Historical Society Guides and Handbooks, 8 (London: Royal Historical Society, 1968), no. 139.

Scharer, Anton. Die angelsächsische Königsurkunde im 7. und 8. Jahrhundert, Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 26 (Vienna, 1982), pp. 274–5.

Stenton, Frank M. Types of Manorial Structure in the Northern Danelaw. Clarendon Press, 1910.

Tinti, Francesca. “The Reuse of Charters at Worcester Between the Eighth and the Eleventh Century: A Case-Study.” midland history 37.2 (2012): 127-141.

Tinti, Francesca. Sustaining Belief: The Church of Worcester from c. 870 to c. 1100. Routledge, 2017.

Wormald, Patrick. “Charters, law and the settlement of disputes in Anglo-Saxon England.” The Settlement of Disputes in Early Medieval Europe (1986): 149-68.

Appendix - Names

+ Ego Offa rex Dei dono propriam donationis libertatem signo sanctæ crucis confirmo .

+ Ego Ecgferð filius regis consensi .

+ Signum Hygeberhti archiepiscopi .

+ Signum Æðelheardi archiepiscopi .

+ Signum Ceolulfi . episcopi .

+ Signum Haðoredi . episcopi .

+ Signum Unu'u'ona . episcopi .

+ Signum [C]yneberht . episcopi .

+ Signum [D]eneferði . episcopi .

+ Signum Ceolmundi . episcopi .

+ Signum Coenwalh . episcopi .

+ Signum Uuermundis . episcopi .

+ Signum Alhheardi . episcopi .

+ Signum Ælfhuni episcopi .

+ Signum Uuiohtuni episcopi .

+ Signum Alhmund abbatis .

+ Signum Beonnan abbatis .

+ Signum Uuigmundi abbatis .

+ Signum Utel , abbatis .

+ Brorda .

+ Esne .

+ Heardberht .

+ Ubba .

+ Bynna .

+ Æðelmund .

+ Uuynberht .

+ Lulling .

+ Alhmund

+ Uuigberht .

+ Ceolmund .

+ Eafing .

Translation

Grant from Offa, King of Mercian peoples to Æthelmund of land in Westbury in the province of huuicciorum.

In the name of the supreme thunderer, who is God blessed forever, amen. By potent kings and the rich men of this world, the rewards of eternal life must be purchased with the deceitful things of this mournful world, which all vanish like a shadow. For this reason, I, Offa, named king by the king of kings, for the rescue of my soul freely grant to Aethelmund, my faithful minister, fifty-five hides of land in the province of the Wiccas, in the place that is named Westbury, near the river that is called Aben, in perpetual freedom, on this condition, that it may be forever free from all tribute to the state, small or greater, and from all services, whether to king or prince, except military service and the making of bridges and the maintenance of defences, because it is necessary for all people that none should be excused from this obligation. The entire synodal council wrote this chart of livery in that very famous place that is called Clobeshoas, whose signs and names are preserved below:

Previous Translation:

In the name of the supreme thundering being who is God blessed forever amen. Through the actions of potent regions and the wealthy men of this earth the rewards of eternal life unnecessarily purchased with the deceitful things of this sorrowful world, all of which vanish in a shade.

As such, I, Offa, ascended to be King by the King of kings in order to rescue my soul freely grant to Æthelmund as my devoted servant fifty-five manentes of workable land in the province of the Huuicciori in the place which is named Westbury near the river that is called Avon in eternal liberty under the condition that it shall be forever free from all tribute to the state, small or greater and from all services, whether to the sovereign or Doyen except military service and the making of bridges and the maintenance of defences due to the necessity of all of the people that none should be excused from this obligation and duty.

This charter of regalia was drafted by the complete Council of the Synod in the famed location called Clobeshoas, with the names of the signatories and their sign to God preserved below:

+ I, Offa, by God’s gift and King confirm my own insignia of the grant with the sign of the holy cross.

+ I ecgfer, the son of the king do hereby agree

+ I, Archbishop Hygeberht

Etc.

There are multiple names over the two pages ranging from senior to a less senior position starting with the King, going to bishops, going to presbyters and then people without rank or title that are listed. See the end of this paper for a list.

Document in Latin

In nominee summi tonantis qui est deus Benedictus in secula amen. Regibus potentibus et humius seculi divitibus cum fallacibus istius lugubri mundi substantiis quae omnia sicut umbra eunanescunt aeternae vitae promia mercanda sunt.

Quapropter ego Offa Rex a rege reguum constitutes terram l.v. Cassatorum in provincial huuicciorum ubi nominator uuestburg prope flumen qui dictur aben Æthelmundo fideli meo ministro pro ereptione animae meae in libertatem perpetuam sub hac condicione libens concede ita ut ab omni tribute paruo vel maiore publicalium rerum et a cunctis operibus uel regis uel principis sit in perpetuum libra preter expeditionalibus causis et pontum structionum et arcium munimentum quid omni populo necesse et ab eo opera nullum excssatum esse. Scripta est autem haec liberatatis kartula ab universio concilio synosali in loco celeberrimo qui nuncupatur clobeshoas.

Quorum signa et nmina infra tenentur.

+ Ego Offa rex deid ono proprian donationis libertatem signo sancta crucis confirmio

+ Ego ecgfer filius regis consensi

+ Signum hygeberhti archiepiscopi

Etc…

[1] Sawyer, no. 139

[2] Westbury-on-Trym, Gloucestershire.

[3] Warren C. Hollister "The Five-Hide Unit and the Old English Military Obligation." Speculum 36, no. 1 (1961): 61-74. Accessed March 30, 2021. doi:10.2307/2849844.

[4], C. Warren Hollister "The Five-Hide Unit and the Old English Military Obligation." Speculum 36.1 (1961): 61-74.

[5] Ibid. p. 61.

[6] Robert Gallagher and Kate Wiles. "The Endorsement Practices of Early Medieval England." The Languages of Early Medieval Charters. Brill, 2020. 230-295.

[7] Patrick Wormald, "Charters, law and the settlement of disputes in Anglo-Saxon England." The Settlement of Disputes in Early Medieval Europe (1986): 149-68.

[8] Stephen Baxter, "Archbishop Wulfstan and the Administration of God’s property" 2004.;. p. 164.

[9] S 139: Regibus potentibus et huius sæculi divitibus cum fallacibus istius lugubri mundi substantiis quæ omnia sicut umbra evanescunt . æternæ vitæ præmia mercanda sunt .PROEM By potent kings and the rich men of this world the rewards of eternal life must be purchased with the deceitful things of this mournful world, which all vanish as a shadow.

[10] Patrick Wormald, "Charters, law and the settlement of disputes in Anglo-Saxon England." (1986). p. 233.

[11] Francesca Tinti. Sustaining Belief: The Church of Worcester from c. 870 to c. 1100. Routledge, 2017.

[12] Francesca Tinti, "The Reuse of Charters at Worcester Between the Eighth and the Eleventh Century: A Case-Study." midland history 37.2 (2012): 127-141.

[13] Francesca Tinti. Sustaining Belief. Routledge, 2017. p. 2.

[14] Anton Scharer, Die angelsächsische Königsurkunde im 7. und 8. Jahrhundert, Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 26 (Vienna, 1982), pp. 274–5.

[15] Catherine Cubitt, Anglo-Saxon church councils c. 650-c. 850. Leicester University Press, 1995.

[16] Stephen Baxter, "Archbishop Wulfstan and the Administration of God’s property." In Wulfstan, Archbishop of York: the proceedings of the second Alcuin conference, pp. 161-205. 2004.

[17] Bede, ed. Plummer, II, 214; Arthur West, Haddan, William Stubbs and David Wilkins. Councils and Ecclesiastical Documents (Oxford, 1869-78).

[18] Claude Morley 1923. "Clovesho - The Councils And The Locality". Suffolkinstitute.Pdfsrv.Co.Uk. http://suffolkinstitute.pdfsrv.co.uk/customers/Suffolk%20Institute/2014/01/10/Volume%20XVIII%20Part%202%20(1923)_Clovesho%20-%20the%20councils%20and%20the%20locality%20Claude%20Morley_91%20to%20106.pdf.

[19] Frederick Levi Attenborough, ed. The laws of the earliest English kings. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 2006.