Many falsely believe that by simply producing more money or redistributing it, we would all suddenly have more wealth. It can come in multiple formats: it can be in the form of cash or alternative instruments, which we see more commonly today. Such instruments include debt and loan obligations. For instance, producing government loans that issue money to businesses creates new money as the entry on the central bank is produced and then replicated across other banks and financial institutions.

Money is simply a means of mapping obligations. It is a way of sending obligations through time. With barter, individuals trade goods and services at a point in time. The scenario can be extended using contracts and simple derivatives such as futures agreements. Here, one individual could trade a cow to be delivered on the same day as the agreement is concluded with another party accepting an obligation to deliver 10 sacks of barley six months later.

Such forms of agreements are in themselves money. The difference is that they are non-standard. It is difficult to open trade between multiple parties when every individual has what is in effect a bespoke form of money. For such reasons, early monetary systems started to standardise. For instance, if barley or some other grain was the common staple that every person would need to accept at some point, then it could become a readily traded asset. As arbitrary documentary assets became available, they would be used for trading. In fact, the first writing and counting systems involved the tracking of commodity assets.

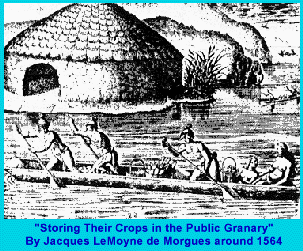

In both early Middle Eastern societies and early Chinese societies, grain stores would be used to collect and allocate the holdings of farmers, ensuring that individuals do not lose valuable foodstuffs to rodents and other sources of loss.

Farmers and merchants would be provided with tally sticks, knotted strings, clay tablets, or in fact similar forms of token. Such tokens would represent the value of grain that had been deposited. At around the same time, contracts for the future exchange of value and even interest-formed payments were developed. With the advent of large-scale storage devices and token notes, to designate ownership of the property being held inside the granary, people quickly started to use the tokens, rather than engaging in direct barter.

Image source: https://www.harappa.com/category/blog-subject/homes?page=1.

The ability to hold a simple token that represented a liquid and tradable asset simplified the exchange of many items, and allowed people to create simple representations of the value of one product against the value of another. If every item needs to be valued independently against another without a single or at least small number of reference commodities, the number of possible interactions quickly grows to an unmanageable quantity. It becomes a factorial calculation.

For instance, if merchant A holds three quantities of three separate items and merchant B maintains another set of three items that differ from A’s inventory, we already have nine possible interactions if we limit ourselves to direct exchanges between the items. If we have partial transfers of each of the inventory items, the scenario becomes even more complex. At the same time, if neither A nor B are trading the commodity grain, but they can account in the same unit, they may simplify the value of all the goods by a common ledger unit.

Money has formed as a universal societal contract in nearly all human societies.

Money as a token system represents rights to quantities of goods or services. In the original form, the amount of money as cash was limited through the ability of one party to directly exchange the required token for an amount of the commodity held under promise. The amount could be either a percentage of the item being stored or a direct measurement such as by weight.

Gerahs, bekahs, shekels, and talents, for instance, represented unit weights. The Hebrew bekah was set with a weight of approximately 6.02 grams, and the shekel with 11.4 grams. The talent relates to 3000 shekels (each at 11.4 grams), and comes to around 75.5 pounds. In biblical references, such weights refer to weights of silver. At a time before coinage, silver, as a precious metal, would be weighed out and measured on scales. Some metals, including copper and silver, would be stretched into sheets or wire, allowing them to be easily cut to the correct weight.

Originally, such values referred to amounts of grain in storage. Over time, as international trade expanded, it became simpler to start using rare metals, which could be easily determined and moved across great distances. As such, trade could open between villages and cities, without the need to transport large quantities of grain back and forth.

Not all monetary token systems ended up being mapped directly to a set weight of a commodity. As explained, some tally systems shared the quantity of a stored item. In other words, the holders would be able to access a percentage of the remaining item at a point in time. For instance, if an individual held 10% of the tally sticks that were available, they might be able to access 10% of the grain in the stores. The system was used in some communities as a form of insurance and distribution. If the commodity was lost or damaged, each rights holder would suffer an equal fate.

Modern fiat money operates similarly to such a system. On one side, we have the amount of issued promissory rights, and on the other, obligations and goods. Every form of money presents, in effect, a rights obligation with respect to other products. Some individuals believe that gold maintains value in and of itself, which is far from accurate. Gold is a marker when used as money for other goods and services. It is not even a completely stable form of money, as some falsely believe. At best, gold can only become a stable form of cash: with a need to be able to repay amounts in gold at later times, the amount of bank lending and borrowing is of course limited.

The amount of money that is available in society at such a point in time balanced against the amount of goods that are available sets the exchange rate of money. It is not a matter of how much money is available in total, or the total money supply, it is about the amount of money that can be treated as unavailable and exchanged money that is unable to be moved or that is held by people who are unwilling to move it. Each of us has a risk preference for holding money. For instance, if we are incredibly confident and know that we will have enough money at any point in time, we do not need to hold more money than we require until our next paycheck. More so, with interest-free periods on many credit cards, many individuals do not have a requirement for immediate cash at all. The amount of money that is required will vary depending on when the debts and obligations of each of the individuals and society come due.

When more money is introduced in the form of direct cash or loans, it may not have an immediate impact. If the amount of goods being sought is limited, then the impact of injecting money could be one of stimulating growth in the short term. Politically, it is an incredibly attractive option. But, such politics works in the short term and at the expense of the long term.

In the long term, the total money supply will reference the total amount of goods as we value items and measure inflation. If the amount of goods is increasing, an increase in the money supply will not be noticeable. If, for instance, in year one 100 units are produced, in year two 110 units are produced, in year three 121 units are produced, and so on, the introduction of a 10% increase in the money supply will, all other things remaining equal, lead to an inflation rate of zero. The problem occurs when the money supply continues to increase but the amount of goods or services has failed to increase at an equal rate.

In such a scenario, more money can be chasing fewer goods and services.

When it occurs, monetary inflation will start, and can skyrocket if the amount of money continues to be produced. In the last century, we have undergone a previously unthought of and unheard-of level of growth. It is what allowed governments to increase the money supply while maintaining low inflation.

The problem occurs when growth stalls: if we continue to increase the money supply and the supply of the amount of goods and services either fails to grow or even falls, inflationary pressure starts to build.

The amount of free money at any point in time references the amount of free goods and services that are available: if we produce less and consume our stockpiles, the amount of money available in society will not have decreased, and may have increased, but the amount of goods and services that are being chased by the same money will have diminished. If we start with 100 units of money and 100 units of goods, then each unit of money remains equal to one unit of goods. But if we now have only 50 units of goods and services available, it will now take two monetary units to purchase one unit of goods. Such is how inflation occurs and what money references.

Money does not have a set value. It does not matter whether you are talking about token commodity money, such as gold, or a more esoteric concept of money in the form of fiat money or banknotes: in both events, the quantity of money gains its value when compared against the quantity of goods.

Even when money was linked to gold, the same simple fact did not change. What gold did was limit the ability for governments and central banks to expand the monetary supply. Even with gold, banks would be able to issue fractional reserve notes against an amount of gold that was held. At no point in history has gold acted as the complete form of money, nor can it do so. Gold, at best, can act as an anchoring point based on the requirement for banks and other organisations to be able to redeem at a point in time. Here, a bank that is too deeply in debt or has extended itself too far and is insufficiently capitalised will be constrained.

Gold was never a cash-based system. Although gold coins have existed, they are too expensive and difficult to transfer in small, daily-use quantities. Gold was used in the settlement and exchange of large-value items. People would not use gold coins to settle small debts. What needs to be remembered here is that the amount of gold in circulation was always far more limited than the amount of money in circulation. It has always been the case, held true at any point in history.

The value of gold lies in the limitations it imposes. Gold formed a system that set a natural bound on the expansion of the money supply. As much as some individuals and governments would prefer a short-term expansion, the necessity to maintain a certain capital allocation limited the ability for both banks and governments to expand monetary financing beyond certain levels. More importantly, gold acted as a universal standard and measuring stick across multiple countries at a single point and multiple points in time for a place or set of goods. The problem with gold stems from the inconsistent discovery of new deposits.

The amount of available gold cannot be adequately predicted, as is the amount of new gold that is injected into the system unstable. Throughout history, discoveries of new gold have radically changed the amount of gold available and, consequently, drastically altered the exchange rate of money to goods. None of such discoveries have been predictable; rather, they have acted as a black swan, radically distorting the global monetary system.

Money and Bitcoin

Bitcoin doesn’t replace banks. It is an electronic cash system and not a banking system. We have moved from the system that involved both banks and cash towards one where cash is disappearing, which is problematic in many ways. Banks don’t replace cash, and Bitcoin doesn’t replace banks. In my white paper, I explained:

Commerce on the Internet has come to rely almost exclusively on financial institutions serving as trusted third parties to process electronic payments. While the system works well enough for most transactions, it still suffers from the inherent weaknesses of the trust based model. Completely non-reversible transactions are not really possible, since financial institutions cannot avoid mediating disputes. The cost of mediation increases transaction costs, limiting the minimum practical transaction size and cutting off the possibility for small casual transactions, and there is a broader cost in the loss of ability to make non-reversible payments for non-reversible services. [Emphasis added]

Cash is not and was never designed for making multibillion dollar payments. They are possible with Bitcoin, but are not desirable outside of a few criminal activities. And even so, when criminal actors come to understand the nature of Bitcoin, they will come to understand that Bitcoin is not good for criminal activities. Bitcoin works best as a system that allows very small transactions and small casual transactions, such as ones that would be seen over a micropayments application on the Internet. The banking and credit card models don’t work for accessing small casual services. Bitcoin will.

Irreversible transactions are not about illicit goods. They are about small transactions that can occur online as if they were carried out in cash. The scenario does not include the sale of illicit goods, such as drugs or child pornography. In both such cases, the economics are skewed towards tracing the perpetrators and coin (bitcoin) allowances. On the other hand, where a small transaction occurs for, say, a valid payment of half a US cent to a web service offering access to a blog, the person who read the page cannot cancel and remove the payment. The reason here is that the cost of enforcement in taking legal action exceeds the benefit of any rational action for half a cent.

In my paper, I talked about fraud. Where merchants no longer need to trust customers by means of a credit card, that can be easily stolen, merchants need no longer “be wary of their customers, hassling them for more information than they would otherwise need”. Even with Bitcoin, “A certain percentage of fraud is accepted as unavoidable,” but, values differ. The consumers will go to the occasional website that will scam them out of a hundredth of a cent, and they will care a lot less. But even such cases will not be widespread, as the requirements to set up and manage servers will limit the number of criminals who can scam people based on small amounts of money.

These costs and payment uncertainties can be avoided in person by using physical currency, but no mechanism exists to make payments over a communications channel without a trusted party.

Here lies the prime reason for Bitcoin. It is not about attacking banks. Very simply, it is a cash-based system that works over the Internet. It is not about replacing intermediaries or what they call trusted third parties; the difficulty with trusted parties is that they increase the minimum level of exchange, which is what Bitcoin solves. Is not digital gold, and it is not an anonymous money source that allows people to buy illicit goods. The purpose of Bitcoin was very simple and focused: Bitcoin is an ordering and timestamp system that allows for the creation of digital cash in a manner that is efficient and effective. Unlike monetary systems based on a trusted third party, Bitcoin can enable transactions that act as cash and that can be as small as a thousandth of a cent.