Segregated Witness (SegWit) was said to be introduced to stop purported errors caused by malleability. The truth of the matter is that it was introduced as a means of producing the Lightning Network (short: Lightning) protocol and changing Bitcoin from a property-based token system to an account-based one. Bitcoin is based on individual indivisible property tokens, known as a satoshi. There are 100 million individual tokens for every nominal coin, known as bitcoin. Because of the form of the register in Bitcoin, it is possible to fully possess civil property — even though bitcoin is intangible and digital. Unlike any other virtual system before, whether in the form of digital cash or mere files, Bitcoin allows a digital file to act as if it was a corporal thing, which provides the ability to possess bitcoin.

The tokens in Bitcoin are not stored on the blockchain, they are registered there. That is, tokens are exchanged between users and eventually registered on the blockchain, which acts as a distributed clearing house and registry or ledger. All changes are journaled, although multiple changes can apply before being written to the ledger. Where an individual or group exchanges Bitcoin tokens (bitcoin), property rights are also exchanged, but until it is registered on the blockchain, a risk remains that one party could ‘double-spend’ and take away the tokens from another.

Bitcoin allows possession, and acts as property as the owner or proprietor of the tokens may exercise power to exclude others. Unlike other digital property, bitcoin can be subject to bailment [1].

The scenario can be achieved by simply sending the coins to the bailee or through the use of a smart contract such as in the form of an escrow agreement. Tokens may be locked in trust subject to the execution of a contract or act, upon which the tokens may be either delivered to the beneficial owner (the bailor [2]) or, should the bailee fail in his or her duty, seized by the bailee.

Bitcoin as indivisible property is a problem for systems like the Lightning Network. You see, the reason for Segregated Witness, which I have hinted at, stems from the fact that you cannot remove the base peg value that is used in a Lightning transaction without destroying the entire channel. Such is also why they made malleability out to be a major security flaw within Bitcoin. It isn’t; malleability is only a security flaw in Lightning-based payment channels, which were never a part of Bitcoin. You see, Lightning is about creating a system that is not built on individual tokens, but rather balances, because they are treated very differently under law. Yet, the Lightning Network cannot work without Bitcoin tokens as the initial seed base. Here lies the greatest flaw of the system. There is no way in a blockchain to remove the property rights associated with bitcoin. Each bitcoin comprises indivisible tokens, which, in turn, present certain legal obligations.

Nemo Dat Quod Non Habet

Nemo dat quod non habet, or, to simplify the Latin phrase, the nemo dat rule, presents the legal principle that “no one gives what they don’t have”.

Bitcoin tokens are property. Following the purchase of bitcoin where you haven’t met customer due diligence (CDD) and know your customer (KYC) requirements and recorded the identity of the person you’re attempting to buy from, you face a scenario where good title does not pass. If stolen bitcoin are passed into a Lightning channel, the purchaser in the Lightning channel does not gain good title. Equivalently, the civil rule of nemo plus iuris ad alium transferre potest quam ipse habet, or, “one cannot transfer to another more rights than he has”, means that it does not matter whether you send bitcoin to a Lightning channel; if the bitcoin are stolen, they cannot be transferred.

Under the Theft Act 1968 in the UK, ““Property” includes money and all other property, real or personal, including things in action and other intangible property”. The definition clearly includes bitcoin.

The consequence is that stolen bitcoin remain property, and if, say, they go into a Lightning channel, it would be possible to issue a freezing order, which we have seen in the UK and Ireland multiple times already, stopping any movement of the coins. Theft is a global crime. There are very few countries that do not see theft as a major indictable offence. Certainly, every country that runs bitcoin exchanges and miners will allow action against thieves and the recovery of property.

Things get more interesting when you consider that there are crimes around the world for the handling and possession of stolen goods. Bitcoin, as I have said, is a series of tokens. Miners are paid with tokens. For the Lightning Network to work, transactions need to be validated and put onto the blockchain by miners. Whenever they are not, or where transactions ‘rollback’ such as in the form of changes that come with malleability, the Lightning Network completely fails.

There is a section of the Theft Act 1968 in the UK that provides legislation analogous to legislation in China, the USA, and many other countries concerning the handling of stolen goods:

Handling stolen goods.

(1)A person handles stolen goods if (otherwise than in the course of the stealing) knowing or believing them to be stolen goods he dishonestly receives the goods, or dishonestly undertakes or assists in their retention, removal, disposal or realisation by or for the benefit of another person, or if he arranges to do so.

(2)A person guilty of handling stolen goods shall on conviction on indictment be liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding fourteen years. [4]

Upon the issue of a freezing order, commercial network nodes are under an obligation not to transact in frozen bitcoin, as they would be upon a proceeds of crime order associated with the coins. Worldwide freezing orders can be issued against many types of assets. Bitcoin miners globally would be restricted from processing frozen bitcoin. But, it goes further: if a Bitcoin miner receives tokens that are stolen, they are handling stolen goods. The Bitcoin miner is likely to have an investment of $100 million or more that can be seized. You see, criminal actors are targeted. When police and other law enforcement officers find a large criminal cartel that is simple to issue an order against, they will sequester goods and arrest the individuals involved. The same $100 million data centre, consider it proceeds of crime.

The biggest flaw in systems where people build on top of Bitcoin without understanding it comes with the fact that the coins are property. Property rights follow even when coins are redistributed. If you move a Bitcoin token through 1,000 addresses, the original owner maintains ownership. When you have BTC1.0, you really have 100 million individual and indivisible tokens, known as satoshi. If you take the BTC1.0 and send it to a miner and onto the Lightning Network with a small nominal fee of 1,000,000 satoshi, transferring 99,000,000 satoshi or BTC0.99, and it turns out that there is a freezing order, proceeds of crime order, or some other notification that alerts to the theft of the tokens, the miner receiving the BTC0.01 fee is handling stolen goods.

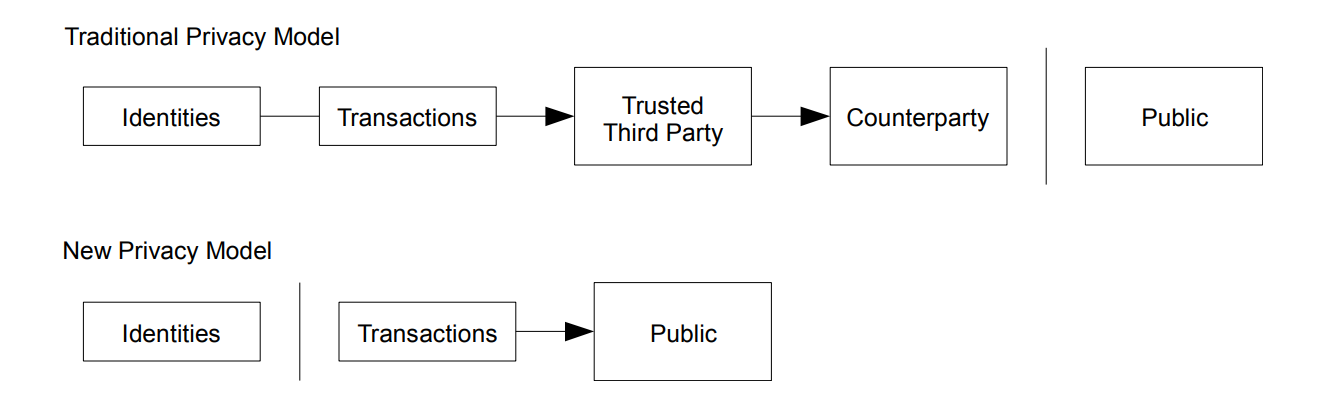

An exchange that handles stolen goods is liable, and will have to pay damages. Bitcoin is not a system without identity; section 10 of my white paper notes identities, which are firewalled from the public network. In other words, individuals on the network are required, by law, to do their own customer due diligence (CDD) and meet the requirements.

When a court issues a proceeds of crime order against bitcoin and the bitcoin are put into a Lightning channel, both the miner who allows the transfer and the Lightning hubs become liable for the handling of the stolen goods.

Stolen property remains the property of the individual whom it was stolen from. If a miner validly transfers bitcoin into a Lightning channel before being alerted to the theft, the bitcoin will be the subject of a recovery or other court order and shall be returned to the individual. Every single individual in the Lightning Network who engaged in the passing of the original stolen bitcoin would be committing a crime. Luckily, the Lightning Network is a highly centralised payment intermediary system, so very few people will be affected.

The scenario requires a reallocation of the tokens. You see, there are very few miners in the Bitcoin network or any of the other networks, such as the BTC and BCH systems. In fact, there are less than 100 nodes on the BTC network. Nodes are miners; a ‘node’ that has never mined a block is not a node. The definition of nodes is given in section 5 of my white paper. If you don’t create and verify blocks, you are not a node; you do nothing. The consequence is that Bitcoin is not distributed because millions of people run nodes, it’s distributed because nobody can change the rules.

The false narrative is that ‘non-mining nodes’ would do anything. They don’t; they follow what miners or real nodes do. They can verify their own transactions and nothing more.

The end result is that Bitcoin miners (and exchanges) will follow court orders. If you want to argue that code is law, remember that the court can order code to be patched. When I introduced the alert key in 2010, it would have allowed a simple manner to stop proceeds of crime and stolen bitcoin being taken. The “hacks” like Cryptsy and embezzlement cases like Mt. Gox would not be viable. It is troubling that such ways have gone on for so long, but 2020 marks the year that law comes to Bitcoin — and all the copies.

As such, and as it is explained in the Bitcoin white paper, honest miners form the 51%, who enforce rules and follow court orders.

Notes

[1] See: https://thelawdictionary.org/bailment/ (accessed 26th March, 2020).

[2] The bailor is the party who bails or delivers goods to another, in the contract of bailment. McGee v. French, 49 S. C. 454, 27 S. E. 487. The bailee is the person to whom goods are bailed, that is, the party to whom personal property (which would include bitcoin) is delivered under a contract of bailment. Phelps v. People, 72 N. Y. 357: McGee v. French, 49 S. C. 454, 27 S. E. 487.

[3] See: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1968/60/crossheading/definition-of-theft?view=plain (accessed 26th March, 2020).

[4] See: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1968/60/section/22 (accessed 26th March, 2020).