In section 9 of the Bitcoin white paper, I defined the notion of a new privacy model.

In my paper, I start by saying how the traditional privacy model works and detail it in an image. In the traditional banking model, many parties distribute PII or, as it is more commonly known, personally identifiable information — a topic I’ve written about many times over the last decade or two.

The traditional model involves the parties sharing their identities with each other and others such as correspondence banks, credit companies, and even processing groups. The same intermediaries, whether they are trusted third parties or counter-parties to the transaction, all end up knowing the details of the individuals involved in an exchange. In the Bitcoin white paper, I’ve mentioned both identities and the ability to keep public keys anonymous outside of those who require knowledge of the transaction. It is not anonymity, it is privacy. It is keeping details away from the public; not those who were involved in the exchange and certainly not those who are required by law to monitor exchanges.

Importantly, where keys are not reused and where every transaction is split into multiple payment amounts and coins, we allow even for the ability to monitor meta data in a manner similar to how a tickertape or stock exchange would aggregate data; everything can be audited without the public knowing all of the information about a transaction. Rather, private information and even transactional data no longer need to be kept isolated from viewing.

One of the key aspects of cybercrime in the past two decades where we have seen rising prevalence is the one of identity theft. In the traditional privacy model, where identity theft is directly linked to cyber criminals’ ability to steal money, transfer assets, and defraud third parties, the necessity to protect identities is paramount. The consequence is a rise in the theft of credit card numbers or other personally identifiable information that criminal groups use to defraud those within society who seek to act within the law.

More importantly, we have to trust information that is gathered through intermediaries and government as to the nature of the economy. We cannot view the transactional flows because to do so would involve releasing information that would leave those people involved in trade vulnerable.

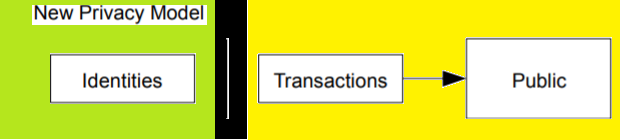

In the new privacy model created with Bitcoin, transactions are no longer private. In order to stop the main problem with digital currencies, double spending, it has been necessary to create a system that announces all transactions publicly and which can be viewed and analysed at will. Privacy can be maintained, but it is no longer associated with the transaction.

The parties to a transaction can calculate new keys that can simultaneously associate their identities and act to identify and authorise parties within organisations, even for purposes of taxation. In the Bitcoin privacy model, identities are firewalled from the transactions and the public, but are not removed. In fact, commercial exchanges and contracting cannot occur without knowledge of the other party.

When I created Bitcoin and wrote the white paper, I intentionally addressed identities in section 9 as we were discussing the parties in a peer-to-peer exchange system. Bitcoin does not remove the need for all third parties. Anyone who thinks so should have a read of Coase’s seminal contribution to economics in his theory of the firm. I would further recommend a reader interested in the topic do further research into Knight’s risk-sharing and agency theories of the firm. Markets do not operate in a costless way. All transactions come with a variety of costs, and at times intermediaries will minimise the costs associated with exchanges even when associated with a system such as Bitcoin. Bitcoin’s seminal achievement is the introduction of a methodology that allows for a new type of transaction, ones that are smaller than would ever be possible using a third party or intermediary.

The exchange of information for under one US cent has never been economically viable in the past without resorting to hidden costs as we see it in the current social media, such as in the form of Facebook or Twitter. While such systems purport to be free, they in reality sell identity.

Many people who have been attracted to Bitcoin falsely assume that perfect decentralisation can be achieved. They parade models of perfect competition with an incomplete understanding of the price system. In such near religious revelations of the price system, they assume all competition is good and also costs less without considering transactional frictional fees. In the debate between mercantilists and free-trade advocates in the call for laissez-faire, debates surrounding competition and the organisation of organisations and firms have devolved into ones of religious fervour. Whilst the debate around the scope of government and the role of the economy and the extent to which we should interfere with it is of interest, the Smithian call towards merely preserving a limited role for the state has changed to one that neglects the cost associated with an unordered system and chaos.

Smith (1776) moved us from a centralised control of the economy into a concept of moderated competition. It differs from extreme decentralisation and the chaotic resource allocations that result from such a system. The irony that few point out is that a system that acts without rules slowly divulges into one of extremely centralised control as those who are most efficient at a point in time gather more resources and use them to take further resources from the competitors. It is but a very restricted form of maximising competition where the actors in the system seek merely to maximise utility or wealth with a complete disregard to the decisions and needs of others. One could say that it is an often parodied dog-eat-dog system. The appropriate name of such a system is ‘perfect decentralisation.’

In a system of perfect decentralisation, only power and the ability to guide, manipulate, or control markets through any means have weight. It is a system where no parameters of the system remain in the control of any actors or institutions and where all authority in any role is misallocated, away from anything other than price.

Coase investigated the scenario when looking at the development of firms in his theory known as the transaction cost approach to the theory of the firm.

Why would a set of individuals engage in the costly managing of the exchange of services through a firm, if they could individually achieve more?

Importantly, one aspect that is overlooked is the informational cost.

Williamson (1991) provided reasoning to detail transactional costs and the development of firms as a consequence of the fact that “the governance costs of internal organisation exceed those of market organisation.”

In his microeconomic model of organisations, profit maximisation or efficiency leads to the substitution of firms for markets. Similarly, there are times where intermediaries such as banks and credit organisations remain more efficient and develop to replace impersonal markets. Even with Bitcoin, the efficiencies gained in removing intermediaries from small and previously unavailable transactions do not scale to a complete removal of all intermediaries. Nor would any system ever be able to do such a task.

It was Marx’s ideal to see complete and pure decentralisation. Marx saw all individuals in a communist world able to act without the firm. Each person would engage in a series of tasks that would allow them to do everything from growing their own food to producing their own tools. It is a common socialist mantra, and was taken up by 20th-century luminaries, including Gandhi. Unfortunately, such a romanticised ideal of the world does not work. As Adam Smith (1776) demonstrated, there are efficiency advantages in specialisation, and some of the gains of specialisation come in the creation of organisational intermediaries. One example is the one of project management. Those who act to pull together distant or misallocated resources and to efficiently budget them in a specialised manner themselves become specialists.

The model used to allocate identity and privacy within Bitcoin is one that maximises informational efficiency. Identity both has value and comes with its cost. Parties involved in transactional exchanges where identity is involved have to act to secure the information associated with the exchange. The cost, liability, and risk associated with its disclosure, theft, and fraud increase the cost to intermediaries, and lower the efficiency of trade and exchange.

Such costs have acted to mitigate the ability to exchange information of small value or even to engage in trade at the level of micropayments. As Bitcoin scales, such costs will decrease, and the ability to exchange previously unthought of items and services will start to evolve.

The new privacy model in Bitcoin does not remove identity. It does, though, alter the need to use identity in a manner that lowers the security of participants and the trade and which increases the risk of disclosure. In allowing exchanges that do not involve trust based on personally identifiable information and easily copied authorisations, Bitcoin creates new forms of exchange and opportunities.

In exchanges, those involved in trade using the new privacy model of Bitcoin maintain identities. Where Alice and Bob seek to engage in a peer exchange, they may now do so whilst only having to store the minimal identity required for the transaction. In small transactions, the risk can be low enough and reputation itself can be of high enough value that the parties will need minimal identification to exchange.

The scripting system within Bitcoin is sufficient to allow even larger exchanges to occur. With the ability to add separate identities and signatories to a transaction, arbitration and escrow can be implemented automatically. In other words, the scripting and contract capabilities that exist within Bitcoin allow the parties to a transaction to determine the method of dispute resolution before they execute in accord. They can do so during the negotiation phase of an agreement.

Such possibilities are achieved through the ability to create unlock scripts that are constructed with a nearly unbounded range of input options and values where if both parties seek to use either mediation or arbitration services, they can do so whilst still maintaining full privacy and even engage in arbitration and mediation practices that do not require the disclosure of personal information. The process can be extended to allow the automation of advanced court systems. For instance, the Singapore State Courts’ Community Justice and Tribunals System launched an “e-Mediation” service that could be automated allowing parties to select the system without having to resort to courts as a first resort.

In such a way, disputes between parties to a Bitcoin-based contract could be solved quickly and with minimal hassle. As such, the disputants would not even be required to attend court, and could file documents online. Extending the scenario further, we could see a world where international trade and commerce could be conducted with distributed jurisdictional options linked to blockchain-based technology and contracting. It would provide much needed governance from within the technology delivered through Bitcoin. Using registered digital certificates for the parties and a mediator, arbitrator, or national court, Bitcoin could be used to integrate smart contracts and DFA (deterministic finite automata) hierarchically allowing for a range of both novel and traditional dispute-resolution procedures that can be appealed and processed within the existing legislative context.

With the recent Court of Appeal decision in Golden Ocean Group v. Salgaocar Mining Industries [2012], the courts confirmed that a series of ongoing electronic communications should be held to be writing and signed documentation per the Statute of Frauds (1677). Combined with cases such as WS Tankship II BV v The Kwangju Bank Ltd [2011], we argue that the use of smart contracts can be extended to encompass many areas of law traditionally only determined in paper and formal dispute resolution. Lastly, we demonstrate that the data-protection provisos of GDPR, that allow for an individual’s right to request specific personal data be erased in certain circumstances or to have data corrected, are easily managed without the permanence of records on blockchain posing a problem.

Well-constructed systems for the private association of keys that are hierarchically determined from an identity key that is never used within the blockchain itself will allow individuals and corporations to interact using new key pairs for every transaction whilst simultaneously being able to provably exchange identity with other people in Bitcoin’s new privacy model.

References

- Coase, R. The Nature of the Firm. Economica. 4 (16): 386–405. Blackwell Publishing (1937). https://www.jstor.org/stable/2626876

- Smith, A. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. 1 (1 ed.). W. Strahan, London (1776).

- Williamson, O. E. Comparative Economic Organization: The Analysis of Discrete Structural Alternatives. Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 36, №2, pp. 269–296 (Jun, 1991). https://www.jstor.org/stable/2393356