To many, it ends up making it seem as if Bitcoin and automated smart contracts could be a way of completely automating the law. It is a fallacy in that we can see common law expressed as a set of predicate expressions that require human intervention.

We will start with the semantics of common-law predicates to both address the “code-is-law” or smart-contract realm, and gain a better understanding of the nature of common law.

The semantics of a word dealing with its meanings.

We can look at the pragmatics as these deal with the relations of words in context and in their use.

Pragmatics include the scope of the speaker’s purpose — social effect, the particular use of the word, and the selection made in the context as related to the words surrounding it in physical context.

- The common law is based on the judicial decisions of cases.

- A case is based on factual situations that are brought before a court in order for a judge to offer a resolution.

- Each particular case brought before a court is separate and representative by different facts.

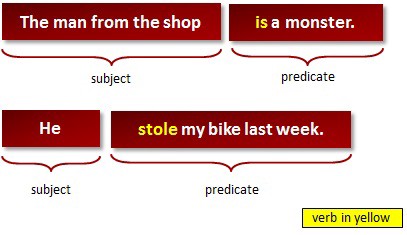

- Each court is in effect provided a set of sentences describing a set of facts. Each sentence selects a proposition, and describes a possible set of worlds and propositions that constitute a more complex proposition.

One difficulty is that facts are often in dispute in a lawsuit. The resolution of factual disputes by a judge or jury through the judicial system provides for the determination of the unique factual setup.

The factual setup creates the conjoined set of propositions. We can see from such analysis that each case involves a uniquely determined set of facts. These facts are expressed as a proposition and a set of possible outcomes, and a legal decision as to whether or not that set of facts is within a particular set of predicate terms that derive some legal predicate is up for dispute.

The predicate is peculiar to common law, our words used for characteristically common legal concepts. Such things include tort, contract, unconscionable. Each of these words has an everyday non-legal meaning; they also have a specific use in legal terms.

Words such as negligent, good faith, and intent may have different uses depending on the context, too.

Predicates have limited sets over what they range. We can say that common-law predicates are semantically unique. From this prima facie it may appear that at the face of common law, a predicate system constrains a judge in reaching a decision. In some other ways we can also argue that the judge is not unconstrained. Common-law judges have the ability to use a variety of different means that are not open to civil-law judges. It enables some extrajudicial flow from the semantic analysis, and judicial decision making is sometimes seemingly inconsistent with other cases.

Such is not in accord with the most positive theories of judicial decision making or theories to do with the economic efficiency of law. We also know that if a judge says, “This is a battery,” then unless a superior court reverses the judge, no matter how ignorant or perverse that judge’s decision may seem, no matter how much the parties and other spectators may disagree, the decision stands.

A judicial decision need not be fixed in stone but can be altered by a higher court.

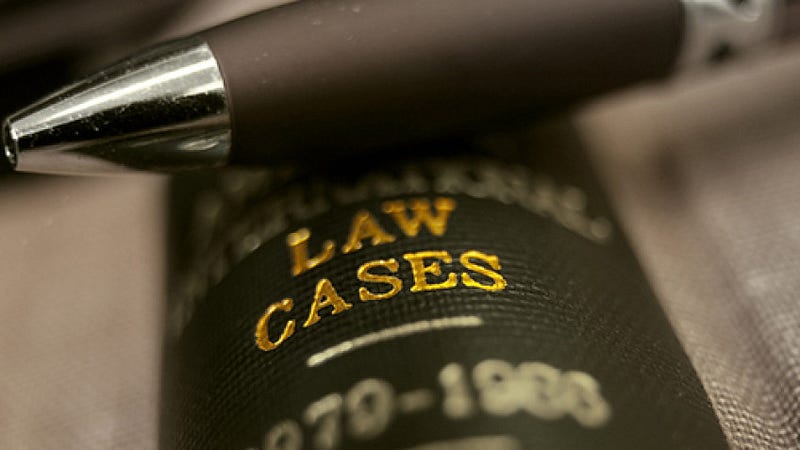

STARE DECISIS

There is no rule of stare decisis laid down by statute in Great Britain. There is the House of Lords practice statement 1966. It is the statement of an intent of a court.

If we look at examples of cases, applications of judicial precedent, we see that simple terms such as printed in one can mean books, journals, and alike, or that printed publications can be something different, such as microfilm in the other. So even when there are seemingly conflicting outcomes, there can be a difference in the predicate model.

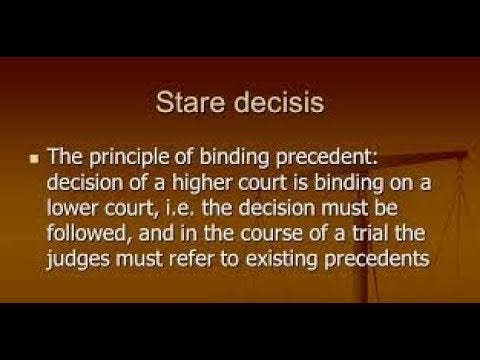

STARE DICTIS

Judges have human fallacy. No judge likes to be overruled. Hence no judge invites reversal.

In the common law, the decisions of judges in disputes brought before them rely on the interaction between other judges and their opinions more than unstatutory enactments.

Judges are not responsible for deciding factual issues, though. Facts may be determined by the judge or jury.

The facts of a legal dispute, once decided — what we can call a case, are a proposition. A conjunction of all the propositions expressing the particular factual findings sets the case.

Judicial function of the common-law judiciary decides whether or not that case is to count as a particular legal predicate.

The difficulty in deciding between stare dictis and stare decisis in cases comes down to not only the determination of facts but the particular determination in different circumstances.

What we see is that the judicial process is far more complex than can be noted in such a simplistic area as a smart contract. In the process, the court needs to be able to adapt their decisions to fit with the requirement of time and also into the decisions of other judges and society as may be seen fit.

Judges adapt not in a revolutionary sweep but rather in an evolutionary manner.

The effect is similar; the common law is let free to do what is needed and moulds itself to social, political, moral, and economic requirements.

The result is that we cannot expect “Code is law.” to hold true.

The requirements for judicial bodies to be able to modify outcomes leave a scenario where the concept of a hard and fast predicate can easily be seen as unfair.