The US Howey case used the Expectation of Profit as an element in International Brotherhood of Teamsters vs Daniel. Daniel involved contributions by employers into a non-contributory pension plan, which was maintained for their employees.

The managers invested the contributed funds to earn profits. Ultimately, these profits would have flowed through to the employees as benefits. The Supreme Court found that the expectation-of-profit element was missing. It focused on what was viewed as a relatively small percentage of the planned assets derived from earnings rather from employer contributions.

As a logical predicate, the court could have decided not to care about actual performance. The focus would have been on reasonable profit expectations of the plan’s beneficiaries.

Many investment schemes go wrong; they do not have any less involvement in the sale of securities for that reason.

United Housing Foundation Incorporated vs Forman is helpful in the US in determining Expectations of Profits. In this, the purchases of interest in a cooperative housing project were to receive financial benefit from their ownership. No profit on a resale of interest was possible. In this case, the interest could only be resold at the original purchase price.

The project leased commercial space to third parties. Any income derived was to be used to reduce the rent on the housing units. The court said this was far too speculative and insubstantial to bring the entire transaction within the Securities act.

Neither Daniel nor Forman should be interpreted as giving promoters leeway structuring investments and investment transactions in a manner that does not involve security offerings.

In Daniel, the court was influenced by the fact that Congress had just subjected pensions to its extensive regulation by ERISA.

In the case of Forman, the obvious motivation of the court and the motivation of the purchasers were to attain a decent place to reside and an attractive price to do so.

The opinion decided in such a way was not to find the security in a social construct. They could have decided that each was a security. SCC vs Edward is a case in which the Supreme Court did wish to find the presence of a security. Note, this is a controlled or regulated security. The scheme involved the sale of pay phones packaged with a 5-year lease pack and management arrangement.

This also incorporated a buy-back agreement. The court rejected its own dicta from an earlier case. The court held the fact that a money-making scheme that offers a contractual entitlement to a fixed rather than a variable return did not prevent it from being a security.

Investment Contract

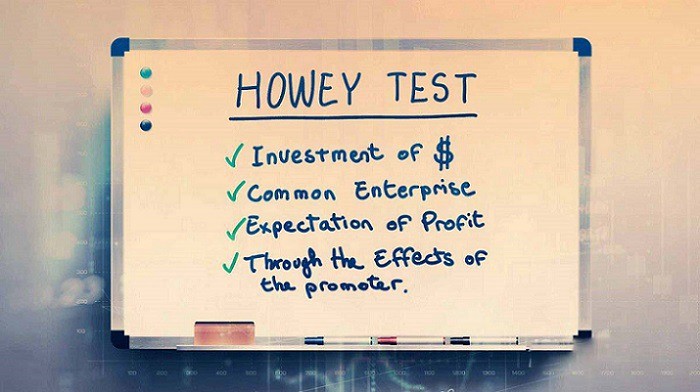

There is confusion around what constitutes an investment contract. The term has no meaning in a commercial context; it is simply a construct of legislators and judges. It is detailed in the Howey Test. The Howey litigation looked at a particular case leading to the Howey Test. We can break down the Howey Test into four predicate subjects.

- The Investment of Money

- Common Enterprise

- Expectation of Profits

- Solely from the Efforts of Others

Investment of Money

The meaning of money can be disposited easily. If we look at ICOs and coin offerings, the US Securities Act covers all offers and sales of securities, regardless of the form of consideration to be exchanged in the bargain. The consideration does not actually have to be money. A court could use money as a short-hand term for something such as cash, cheques, or other negotiable instruments.

It can be anything that would constitute liquid consideration. For an investment to exist, one must put out consideration with the hope of financial return.

The most important case in such a matter in the US for the meaning of investment is International Brotherhood of Teamsters vs Daniel. The Supreme Court in the case had to determine whether an investment contract existed where employers under a collective bargaining agreement made contributions.

Common Enterprise

There are two separate and disparate formulations of Common Enterprise. These have emerged through cases in the Courts of Appeal.

The first is vertical commonality. This focuses on the community of interest of an individual investor and the manager of the enterprise.

The other is horizontal commonality. This concentrates on the interrelated interest of the various investors in a particular scheme.

When considering Common Enterprise as an element as per the Howey Test, it can be useful to note that courts have identified different versions of vertical commonality.

One version is known as strict vertical commonality. In strict vertical commonality, it is required that the fortunes of the investor be linked to the fortunes of some other party.

In another version, which is known as broad vertical commonality, a requirement that the fortunes of the investor to be linked to the effort of another party exists such that it can be expected to accept horizontal commonality, if it exists.

Solely from the Efforts of Others

This is an element of the US Howey test that comes with a question of whether investors are passive or otherwise. Such cases of pyramid schemes where, once brought into the scheme themselves, the other party is outlooking for prospects to bring them into, sales meetings run by promotion companies can be incorporated.