Introduction The Bill of Lading is a document unique document as its negotiability fulfils several purposes. These documents have led to a range of instruments and conventions within international trade. Arrangements which owe their basis of the negotiability of the Bill of Lading are now common place. For these to function as anticipated, the actual and original Bill of Lading must be present through the sale, purchase, letter of credit processes at each stage as the goods on the voyage progress. The system fails when this does not occur. This has led to the use and development of the Letter of Indemnity in international trade.

A Letter of Indemnity is a written duty of a shipper to indemnify a carrier for the liability that the carrier could lay itself open to through the issue of a clean Bill of Lading when the cargo received was not in fact that which was stated on the bill of lading.[1]

Although they are not the ideal solution, Letters of Indemnity are common throughout international shipping. As commercial activity extends, these instruments are being increasingly utilised in the carriage of goods by sea. They may also be identified as letters of guarantee and as counter-letters. Letters of indemnity are employed as either Letters of Indemnity issued at shipment, or Letters of Indemnity issued at discharge. The later are also identified as letters of guarantee.

One of the main issues with the application, scope and limits of any Letter of Indemnity is the extent to which rights and obligations created through the use of letters of intent fail to match those provided by the Bill of Lading.

The failure to produce a Bill of Lading To understand the scope and application of a Letter of Indemnity it is also necessary to address Bills of Lading. These documents are derived from antiquity in English Common law where they have attained prominence by virtue of ancient mercantile custom[2].

Letters of Indemnity are frequently employed in situations where passage has not concluded according to the stipulations contained within the Bill of Lading. For instance, this could include an alteration to the discharge seaport. Most Letters of Indemnity are issued to procure the release of a consignment when the Bill of Lading is deficient or unavailable. In situations where the receiver or final purchaser is not capable of tendering a Bill of Lading to the carrier in order to obtain the release of a consignment, a Letter of Indemnity may be issued. Although common in most seaborne trade, fungible transactions such as the crude oil trade that are reliant on quick voyages and utilise compound sale and purchase contracts deploy these instruments most frequently.

Letters of Indemnity have been used to fulfil the three primary functions of a bill of lading[3]. These include: · Use as a receipt; · To provide evidence of a contract of carriage; · To supply documentation demonstrating title in the goods.

Letters of Indemnity as a Receipt Letters of Indemnity have been used in place of a Bill of Lading as receipts. By stating the particulars of the consignment and the expected order and condition within which it was shipped, this instrument[4] is can act as evidence of the condition of a consignment as against the shipper and may also act as evidence as against third parties.

Evidence of a Contract A Bill of Lading alone does not constitute a contract. It can be used as evidence of the contract. Generally the Bill of Lading will either incorporate the Hague or Hague-Visby Rules[5]. A bill will include either the full terms or incorporate the carriers’ standard terms. A Charter-party bill will explicitly incorporate the Charter-party terms.

Under the Hague[6]/Hague-Visby Rules[7], there is:

- An obligation on the shipper to use due diligence to render the vessel seaworthy prior to and at the commencement of the voyage[8] and a duty on the shipper to maintain the shipment[9] with care.

- A package limitation[10].

- A time limit of one year in which the consignment’s owners can initiate a claim[11].

- Primarily, any contract formed using the Hague-Visby Rules stops the shipper from contracting out of the rules. Although it is possible to increase obligations above those set out by the Hague-Visby Rules, the shipper cannot decrease the obligations. A clause which contends this will be void[12].

Demonstrating title in goods A Bill of Lading is a receipt for goods, a “control document”[13] which acts as a contract to carry and is also “the key to the floating warehouse”[14]. “A Bill of Lading is a commercial document of dignity[15] and integrity based on good faith”[16]. As such it ties several contracts; the sale contract, the shipping contract, the letter of credit and the pledge and any additional security arrangements.

A Letter of Indemnity at shipment is, “a written undertaking by a shipper to indemnify a carrier for any responsibility that the carrier may incur for having issued a clean Bill of Lading when, in actual fact, the goods received were not as stated on the bill of lading”[17]. The courts often exemplify this practice as fraudulent and have had unsympathetic remarks regarding these practices: “Antedated and false bills of lading are a cancer in the international trade. A Bill of Lading is issued in international trade with the purpose that it should be relied upon by those into whose hands it properly comes — consignees, bankers, and endorsees. A bank that receives a Bill of Lading signed by or on behalf of a shipowner (as one of the documents presented under a letter of credit) relies upon the veracity and authenticity of the bill. Honest commerce requires that those who put the bills of lading into circulation do so only where the bill of lading, as far as they know, represents the true facts”.[18]

The problem of whether such letters are legitimate and enforceable with consideration to the issuer of the letter remains as unsettled jurisprudence. A broad uncertainty in the law and between legal scholars remains as to whether situations exists as to where it would be permissible for a carrier to agree to a letter of indemnity.

Clean bills of lading issued in exchange for Letter of Indemnity, and antedated bills of lading that are issued in exchange for Letter of Indemnity should be distinguished. A Bill of Lading is antedated when the date on the bill is advanced forward of the date of shipment. “Shippers often put pressure upon carriers, their masters and ship’s agents to state on the Bill of Lading a date of shipment not corresponding to the true loading or shipment date but instead to insert a date which coincides with a documentary letter of credit or in order to bring the shipment within the period of a subsidy or quota”[19].

Antedated bills of lading normally do not include misleading descriptions of the goods, only an incorrect date. A shipper that predates a Bill of Lading with forethought is engaging in fraudulent practices[20]. Both fallaciously clean bills of lading and antedated bills of lading have been condemned by the courts.[21] While the courts have responded comparably to each practice, distinctions do exist. Both the Hague/Visby Rules[22] and the Hamburg Rules[23] include a provision on estoppel shielding a guiltless third party from a falsely clean bill of lading. Antedated bills of lading have few legislative protections[24].

There is little if any law that implies that the contract could be impacted when delivered to the right party. The law relates to the circumstances where there has been an incorrect delivery. What little law there is concerning this is primarily Australian and is only persuasive authority in the UK.

The Letter of Indemnity is an independent contract, but does not make an independent misrepresentation[25]. A shipper is at liberty to rely on a Bill of Lading “time bar” even if goods are wrongly delivered under a Letter of Indemnity[26]. In cases where the shipper has negligently delivered without the production of a Bill of Lading can still place reliance on the package limitation.[27]

English law permits the party that takes delivery under a Letter of Indemnity at liberty to bring suit against the shipper if the purchase contract entitling the eventual custody of the Bill of Lading was entered into prior to delivery of the goods.[28]

Letter of Indemnity Ideally the Bill of Lading should reach the destination at the discharge port at the same time as the ship. In many cases this does not occur and release is taken as against a Letter of Indemnity. Under English law, a Master is not required to grant delivery under a Letter of Indemnity[29] unless ordered by the Court[30]. It is acceptable for the Master to necessitate that the original Bill of Lading be offered. Charter-party terms may however require the Master to deliver against a Letter of Indemnity. In many cases where the receiver is not creditworthy, it will be a requirement that the Letter of Indemnity is signed by a bank.

Where a Bank countersigns a Letter of Indemnity without qualification, it is likely that they are signing as an indemnifier and not just a verifier of a customer’s signature. Carriers should make sure that any Letter of Indemnity is issued with the Indemnifiers authority[31].

The P&I Clubs[32] do not consider delivery of a shipment without a Bill of Lading as being a reciprocal risk. If a shipper gives such a Letter of Indemnity, it effectively replaces any P&I cover.

Presenting a Letter of Indemnity (“an Indemnifier”) will leave the party collecting the goods liable to indemnify the shipper both against an action from a Bill of Lading possessor and for expenditure sustained by the vessel including direct costs such as the provision of security or discharge from arrest or economic costs akin to loss of hire[33]. If damages are an insufficient remedy, the Court can order specific performance[34].

Several issues come about through the use of Letters of Indemnity. Some of these that are noted by Prof Tetley [35] include: 1. The effect as against third parties and the rights that arise;

2. The rights and obligations between parties to the letter of indemnity;

3. Complications which arise when there is damage to the cargo during carriage;

4. Complications which arise when the carrier is both the charterer and the ship-owner taken together and only one of those persons has issued the Letter of Indemnity.

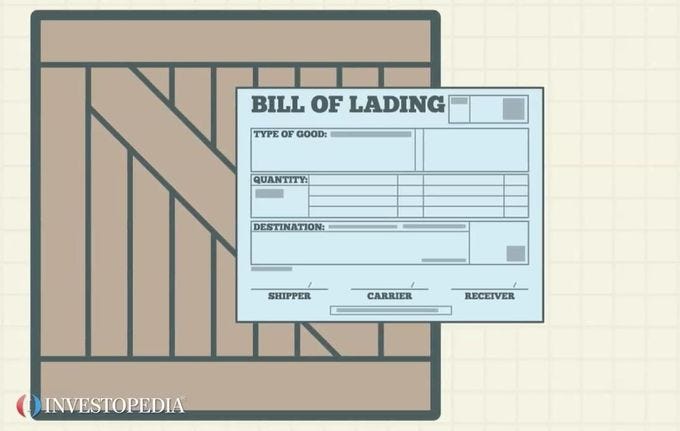

Validity with Regard to Third Parties A third party is an individual or organisation, not being the shipper or the carrier, who has become innocently involved with the Bill of Lading contract without foreknowledge concerning the fallacy of the assertions in the Bill of Lading or the letter of indemnity. As the third party was not involved with the Letter of Indemnity contract, it ought to consequently have no consequence with regards to the third party.

In the common law, Letter of Indemnity between the shipper and the carrier have no effect on third parties acting in good faith.[36] As discussed above, the common law, as well as statutory law, ensures through the doctrine of estoppel that Letter of Indemnity cannot be used as evidence to show that the goods were damaged prior to loading in defence against a third party’s claim. Letters of indemnity have been considered illegal on several occasions, and thus unenforceable against anyone.[37]

Validity between the Carrier and the Shipper A letter of indemnity is a prima facie binding contract. The carrier should be able to take action against the shipper to recover any costs sustained through use of the clean bill of lading. Issues arise, as the carrier and the shipper are jointly parties to the same deceit. Many jurisdictions have found Letters of Indemnity invalid as against the shipper.[38] Some jurisdictions have sustained the carrier’s allegations against the shipper supported by the letter of indemnity.[39]

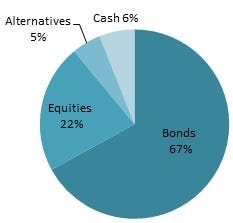

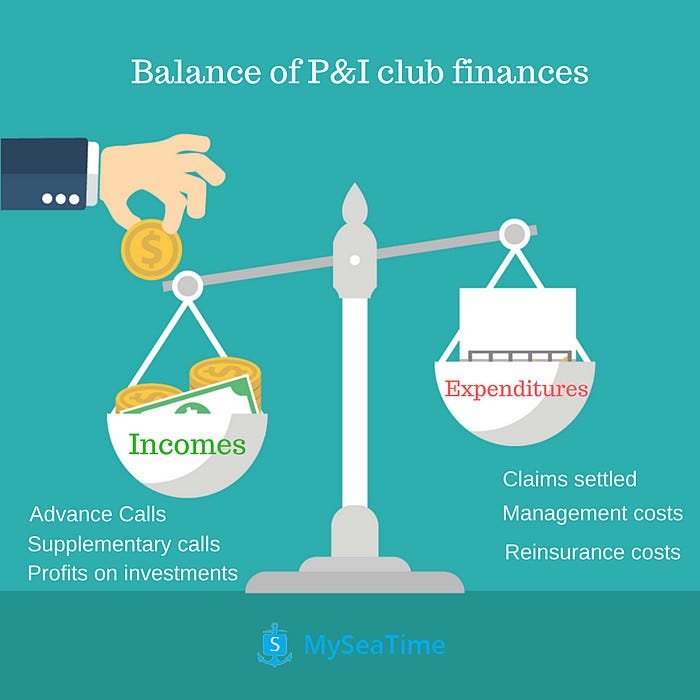

P & I Clubs P & I Clubs[40] are “mutual non profit making insurers which offer shipowners cover for their contractual and third party liabilities: injury or death of crew or passengers, loss of cargo, collision damages to vessels, damage to the environment, etc”.[41] P & I Clubs do not charge premiums, and rely on “calls” on each vessel for payment of a certain rate per ton. This is paid proportionally first at the commencement of the year then with a remainder to be paid subsequent to the assessment of the costs covering the actual losses for that period.[42] To acquire cover from a P & I Club a shipowner must join as a member of the club. This starts their contractual relationship, governed by the membership rules of the particular club. There are fourteen P & I Clubs currently in business. These are mostly positioned in England, Scandinavia, and the Caribbean[43].

P & I Clubs view the custom of antedating Bills of Lading in the same way as of falsely issuing clean bills of lading. “All liabilities resulting from ante-dating or post-dating of a Bill of Lading are excluded from P & I Club cover.”[44] The clubs deem members who consciously issue incorrectly dated Bills of Lading to be acting fraudulently. The clubs will not indemnify them for liabilities that consequently arise.[45]

P & I Clubs specifically recognise and prohibit the custom of antedating Bills of Lading as one of the exclusions to club cover with deference to cargo liabilities[46]. Contrasting issues concerning the state or quantity of the cargo, indisputable uncertainty as to the date of sailing is unlikely. As such, P & I Clubs have not proposed any suggested actions in such circumstances.[47]

A Change of destination and Letters of Guarantee The standard form Letter of Indemnity for Change of destination is comparable in structure to the Letter of Indemnity for non-production of the Bill of Lading or Letter of Indemnity for the non-presentation of Bills under a letter of credit.

Letters of Indemnity, in the form of a letter of guarantee are offered at discharge by consignees unable to make available the original bill of lading. The letter of indemnity “…is designed to provide a remedy for a ship-owner, where the master releases cargo at the request of a party, in respect of claims which may be brought as a consequence of such release”[48]. This custom has grown ever more widespread over the years. Short-haul shipping particularly makes use of these instruments.

Letters of indemnity issued at discharge are designated by some authorities as letters of guarantee.[49] A letter of guarantee is characterised as, “a letter…given at discharge and delivery by a consignee who is unable to surrender original bills of lading which have been issued but lost…[and is] a security or suretyship agreement”[50]. The courts frequently do not use specific terminology whilst referring to a letter of indemnity given at discharge, and simply refer to Letter of Indemnity generally.[51]

The Banking System and Financing Requirements The banking system generally finances international trade.[52] The securing of international disbursements is most often completed using of documentary credits.[53] Transactions normally have the buyer request their bank initiate a credit in the name of the seller. To draw on this credit, the seller must ship the cargo as contracted and present the bank with the suitable documents.[54] The particulars of these instruments is reliant on the precise contractual requirements. A usual C.I.F. contract (cost, insurance, freight) would require the seller to submit:

i) The original Bill of Lading,

ii) A valid insurance policy for the goods whilst in transit, and

iii) The sales invoice as originally agreed.[55]

Documentary credits constrained in that the documents (including the Bill of Lading) are required to be “clean” and “unadulterated”.[56] As a consequence carriers frequently come under severe pressure to issue clean Bills of Lading in order that the seller or shipper is able to tender a Bill of Lading conforming to the documentary credit requirements and thus be paid.

UCP 500/600 or “The Uniform Customs and Practice for Documentary Credits”[57] is the standard format for documentary credit transactions used within international trade. Article 32 covers the requirement for a clean Bill of Lading though “clean transport documents”.[58]

(a) A clean transport document is one which bears no clause or notation which expressly declares a defective condition of the goods and/or the packaging.

(b) Banks will not accept transport documents bearing such clauses or notations unless the credit expressly stipulates the clauses or notations which may be accepted.

The date on which the cargo was shipped is also a matter of principal significance. Documentary credits regularly require that the merchandise be shipped prior to a specific date. Failure being that the bank will not acknowledge the documents tendered. The date of shipment requirement has led shippers to influence carriers to agree to accept a Letter of Indemnity as offset for antedating the Bills of Lading[59]. This custom of antedating bills of lading is in effect fallaciously dating Bills of Lading to signify that the consignment was shipped in advance of the actual time. This is a fraudulent act equivalent to the issue of a clean Bill of Lading for spoilt goods.[60]

Fraud English law tends to deal with complicity between a shipper and a carrier to construct an exchange of clean bills of lading for a letter of indemnity which results in the consignee being held liable to the or endorsee though the torts of deceit and negligence or fraudulent misrepresentation.[61] In a commentary on the sway of continental Europe on the law of the UK, Ibbetson stated: “there was still a degree of disharmony between [England and] continental European systems, where the requirements of good faith and fair dealing were far more deeply entrenched, but in 1994 these differences were smoothed out, at least so far as consumer contracts were concerned, by providing that all such contracts should be subject to a general requirement of ‘fairness’”.[62]

The International Chamber of Commerce lists four types of frauds in Letters of Indemnity[63]: 1. Falsified documents, the consignment being non-existent, 2. Goods are of inferior quality or quantity, 3. Same consignment is sold to two or more parties, and 4. Double bills of lading are issued for the same consignment.

The English common law habitually resists any universal obligation of good faith and the accompanying obligations. In particular, the conception of a general duty to inform or the obligation to disclose has been neglected by the common law.[64] Jenkins v. Livesey[65] (House of Lords) promoted the customary perspective held by the common law.

It should be noted that “…academic writers continue(d) to press for some generalisation of the circumstances in which such duty [to notify or of disclosure] arose, moving towards though not necessarily reaching, the principles of good faith in negotiations widely recognised by continental legal systems”.[66]

The exchange of a Letter of Indemnity for a clean bill of lading at shipment is thus a deceitful exercise. It undermines the reliability of bills of lading: “Honesty and integrity in relation to the signing of receipts for goods the subject of bills of lading is essential if persons engaged in international trade are to have any confidence in documents which play such a vital role in relation to the authorization of the payment of money. If receipts are signed dishonestly or in bad faith, the confidence of the international trading community is undermined and a whole system that was designed to work for the benefit and protection of both parties to a transaction such as this will be called into question”.[67]

Letters of Indemnity continue to be issued in exchange for clean Bills of Lading even though the courts disapprove of the custom[68] and academics have written against it.[69]

Notwithstanding the danger that the carrier will be accountable to the shipper should the shipper sue, carriers will frequently obeisance to the demands of the shipper who requires clean shipped bills of lading in order to be remunerated. Even where a carrier receives a Letter of Indemnity in return, it may not be reassuring as numerous jurisdictions decline to execute the letter of indemnity contract.[70]

It remains the case that a carrier could escape responsibility for a fraudulent action. It has been suggested that a “particularly nefarious fraud has emerged” through the Letter of Indemnity.[71] A carrier could assert an exception (e.g. as inadequate bindings) leaving the consignee and underwriters to remain unaware of a Letter of Indemnity unless action is commenced. They may remain utterly unaware of its existence.[72]Consignees are frequently naive to the possible existence of a Letter of Indemnity. Even when they discover it, the difficulty of establishing an alleged fraud remains.[73]

The requirements of the tort of deceit are that: “Fraud is proved when it is shown that a false re

presentation has been made, i) Knowingly, ii) Without belief in its truth, or iii) Recklessly, careless whether it be true or false….”[74] “If the false statement was made knowingly and that intention is proved then the basis for liability for the tort of deceit is established”.[75]

Evans LJ in Standard Chartered Bank v Pakistan National Shipping Corporation of the English Court of Appeal held in the circumstances where a carrier fabricates a false bill of lading:

“It is clear, in my judgment, that the shipowner would have no defence to the bank’s claim if the master or agent issued a false antedated Bill of Lading in the genuine though careless belief that it would facilitate the particular transaction or maritime trade generally [he] believed he was justified in doing so or that no harm would result”.[76]

Conclusion Letters of Indemnity are a commonly used instrument within international commerce that is unlikely to vanish any time soon. However, using them in order to secure clean Bills of Lading is a practice that should be discouraged. In spite of legal sanctions this custom remains in common use. Shippers whose wares fail to satisfy the requirements of the documentary credit, the contract of sale, and other commercial instruments ought to be required to come to an arrangement with the consignee or other party to the sale agreement in situations where they cannot convey the merchandise using claused or foul Bills of Lading.

Engaging the carrier to aid in the commission of a deception on an innocent third party is deplorable. It should not be endured by the courts or the shipping industry. The notion of acceptable situations in which one can receive a Letter of Indemnity, or “proper Letter of Indemnity”, only to aggravates the dilemma, resulting in the courts scrutinising the intrinsic worth of every case instead of merely condemning the custom.

The inclination of writers and courts to use the terms Letter of Indemnity issued at shipment and Letters of Guarantee issued at discharge should be distinguished (even though they are both indemnity contracts). These are essentially dissimilar instruments and the transposing of the terminology has led to perplexity and misunderstandings of the dissimilarity between these instruments. Letters of Indemnity and Letters of Guarantee hold separate purposes which when scrutinized draw attention to separate inconveniences and limitations of the law and within the transport trade in general.

As Prof. Tetley argues; “Even when a Letter of Indemnity is issued in seemingly good faith, it can cause confusion and hardship”[77].

Bibliography 1. Anderson, C. (1975) “Admiralty Law Institute: Symposium on Charter Parties: Time and Voyage Charters: Proceeding to Loading Port, Loading, and Related Problems” 49 Tul. L. Rev. 880 2. Beatson, J. (1998) Anson’s Law of Contract, Oxford University Press, Oxford 3. Beatson, J. “Has the Common Law a Future” [1997] CLJ 291 4. Chan, F. (1999) “A Plea for Certainty: Legal and Practical Problems in the Presentation of Non-Negotiable Bills of Lading” 29 Hong Kong L. J. 44 5. Derrington, S & White, W. (2002) “Australian Maritime Law Update: 2001” 33 JMLC 275 6. Dromgoole S. & Baatz Y (1992) “Interest in Goods” (2nd Ed) Chapter 22 7. Gaskell, N. et al., (2000) “Bills of Lading: Law and Contracts”, LLP, London 8. Hazelwood, S.J. (2000) “P & I Clubs: Law and Practice”, 3rd Ed. LLP, London 9. Howard, T. & Davenport, B. (1996) “English Maritime Law Update 1994/95” 27 J. Mar. L. & Com. 427 10. Ibbetson, A (1999) “Historical Introduction to the Law of Obligations”, Oxford University Press, Oxford 11. International Institute for the Unification of Private Law, (1994) UNIDROIT Principles of International Commercial Contracts. Available Online at: http://www.unidroit.org/english/presentation/main.htm 12. Keily, T. (1999) “Good Faith and the Vienna Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG)” 3 Vindobona Journal of International Commercial Law and Arbitration, 15 13. Myburgh, P.A. (1995) “Current Developments Concerning the Form of Bills of Lading — New Zealand” in Ocean Bills of Lading: Traditional Forms, Substitutes, and EDI Systems, A.N. Yiannopoulos (Ed.), Kluwer Law International, The Hague, 1995, 237 14. Nicholas, B. (1989) “The Obligation to Disclose Information” in Contract Law Today, D.R. Harris and D. Tallon (Eds), Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1989, 169 15. Parker, B. (2003) “Liability for Incorrectly Clausing Bills of Lading” [2003] LMCLQ 204 16. Rutten, Lamon (UNCTAD), (2004) “A Primer on New Techniques Used By The Sophisticated Financial Fraudster (With Special Reference to Commodity Market Instruments)” UNCTAD/DITC/COM/39 (7th March 2003) UNCTAD secretariat 17. Sharpe, D. (1995) “Recent Developments in Maritime Law” 19 Mar. Law. 301 18. Tetley, William (1985) “Maritime Liens & Claims”, 1st Ed., 1 19. Tetley, William (1994) “International Conflict of Laws”, 1st Ed., 20. Tetley, William (1998) “Maritime Liens & Claims”, 2 Ed., 21. Tetley, William (2003) “International Maritime and Admiralty Law”, 1st Ed., 2003 22. Tetley, William (2004) “Glossary of Maritime Law Terms”, 1st Ed., viewed at: http://www.mcgill.ca/maritimelaw/glossaries/maritime/ 23. Tetley, William (2004) “Good Faith in Contract, Particularly in the Contracts of Arbitration and Chartering (Corrective vs. Distributive Justice)” 35 JMLC 561–616. 24. Tetley, William (2004) “Letters of Indemnity at Shipment and Letters of Guarantee at Discharge” [2004] ETL 287–344. 25. Todd, P. (1990) “Modern Bills of Lading”, Blackwell law, Oxford 26. Weale, John (2004) “Letters of Indemnity: Some Practical Considerations” Maritime Arbitrators of Canada 27. Wilson, J.F. (2001) “Carriage of Goods by Sea”, 4th Ed. Longman, Harlow, UK 28. Yiannopoulos, A.N. (1995) “XIVth International Congress of Comparative Law: Current Developments Concerning the Form of Bills of Lading” in Ocean Bills of Lading: Traditional Forms, Substitutes, and EDI Systems. A.N. Yiannopoulos (Ed.), Kluwer Law International, The Hague, 1995, 3

Cases Alimport v. Soubert Shipping Co. Ltd. [2000] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 448 (Q.B. Com. Ct.) Amann Aviation Pty Ltd. v. Commonwealth of Australia (1991) 66 ALJR 123 (H.C. Aust.) Barclay’s Bank Ltd. v. Customs and Excise [1963] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 81 (Q.B. Com. Ct.) Berisford Metals Corp. v. S/S Salvador 1986 AMC 874 (2 Cir. 1985) Collern & Co. Ltd v. China Ocean Shipping Company [1993] P & I International 16 (Sup. Ct N.S.W.) Compania Naviera Vascongada v. Churchill [1906] 1 K.B. 237 (K.B. Div.) Demsey & Associates v. S.S. Sea Star, 1970 AMC 1088 (S.D.N.Y. 1970) Derry v. Peek (1889) 14 A.C. 337 (H.L.) Donahue v. Stevenson [1932] AC 562 (H.L.) East West Corp. v. DKBS 1912 [2003] 2 All ER 700 (C.A.) Encyclopedia Britannica v. SS Hong Kong Producer 1969 AMC 1741(2 Cir. 1969) Hedley Byrne & Co. Ltd. v. Heller & Partners Ltd. [1963] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 485 (H.L.) Hunter Grain v. Hyundai, (1993) 117 ALR 507 (Fed Ct, Aust.) Jenkins v. Livesey [1985] AC 424 (H.L) Kwel Tek Choa v. British Traders and Shippers Ltd [1954] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 16 (Q.B. Com Ct.) Leamthong v Artis [2004] EWHC 2226 Lickbarrow v Mason (1794) STR 683 Motis Exports Ltd. v. Dampkibsselskabet Af 1912 [1999] 1 Lloyd’s Rep 837 (Q.B. Com. Ct.) Pacific Carriers Ltd. v. Banque Nationale de Paris, [2001] N.S.W.S.C. 900 (October 16 2001) (Unreported) (Sup. Ct. N.S.W.) Pacific Carriers v BNP Paribas (High Court of Australia 5th Aug 2004) Peer Voss v. APL Co. Pte Limited [2002] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 707 (Singapore C.A.) Pickard v. Spears (1837) 112 E.R. 179 (H.L.) Renard Constructions Pty v. Minister for Public Works (1992) 26 NSW LR 234 (NSW C.A.) Sanders v Maclean (1883) 11 QB 304 at 341 Standard Chartered Bank v. Pakistan National Shipping Corporation and Others (№2) [1998] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 684 (Q.B. Com. Ct.) The Aegean Sea [1998] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 39 (Q.B. Com Ct.) The Carso 1930 AMC 1740 at p. 1758 (S.D. N.Y. 1930). The Ines [1995] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 144 (Q.B. Com Ct.) The Nea Tyhi [1982] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 607 (Q.B. Com. Ct.) The New York Star [1980] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 217 (P.C) The Rafaela S [2003] EWCA Civ 556,[2003] All E.R. (D) 289 (Apr.) (C.A.) The Sagona [1984] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 194 (Q.B. Com. Ct.) The Saudi Crown [1986] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 261 (Q.B. Adm. Ct.) The Stettin (1889) 14 P.D. 142 The Sormovskiy 3068 [1994] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 266 (Q.B. Adm. Ct.) The Stone Gemini [1999] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 255 (Fed. Crt., Aust, NSW Adm.) The Zhi Jiang Kou [1991] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 493 (C.A. N.S.W.) United Baltic Corp. v. Dundee Perth & London Shipping Co. (1928) 32 Ll. L. Rep. 272 United Philippine Lines, Inc v Metalsrussia Corp. Ltd. 1997 AMC 2131 (S.D. N.Y. 1997) Statues and Regulations Bills of Lading Act (1855) 18 & 19 Vict. c. 111. (U.K.) Carriage of Goods by Sea Act 1992, U.K. c. 50 Limitation Act 1980, U.K Misrepresentation Act 1967, U.K. c. 7 Pomerene Bills of Lading Act 1916, 49 U.S. Code 102 Protocol to Amend the International Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules of Law Relating to Bills of Lading, Brussels, February 23, 1968 Rome Convention 1980 E.E.C. 80/934, signed at Rome, June 19, 1980 Swedish Maritime Code, 1994, 2nd Ed. Andrea Upplagan T.O.M. 30 June 2000, Stockholm Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1994, U.K United Nations Convention on the Carriage of Goods by Sea, Hamburg, March 31,1978 United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, Vienna, April 11, 1980 U.S. Carriage of Goods by Sea Act (COGSA), April 16, 1936, ch. 229, Sec. 1, 49 Stat. 1207

Footnotes [1] United Philippine Lines, Inc v Metalsrussia Corp. Ltd. 1997 AMC 2131 at p. 2133 (S.D. N.Y. 1997). In this case, a letter of indemnity was issued for this purpose. [2] Lickbarrow v Mason (1794) STR 683; [3] Bowen LJ’s judgment in Sanders v Maclean (1883) 11 QB 304 at 341. [4] The Hague-Visby Rules state that a Bill of Lading is an adequate receipt. An indemnity given by the shipper to the carrier is illegal and ineffective when the carrier has made an intentional misrepresentation about the state of the cargo. The Hague-Visby Rules do not contain detailed provisions regarding the legality of the custom of issuing clean bills for defective merchandise against a letter of indemnity from the shipper. [5] Situations where the Bill of Lading may contain neither of the Hague, Hague-Visby Rules or even the Hamburg Rules are atypical (the Hague-Visby rules are most commonly used). [6] “The International Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules of Law relating to Bills of Lading” was signed at Brussels on the 25th August 1925 [7] “The International Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules of Law relating to Bills of Lading” was signed at Brussels on 25th August 1924 as amended by the Protocol signed at Brussels on 23rd February 1968 and by the Protocol that was signed at Brussels on 21st December 1972. [8] Article III, Rule I [9] Article III Rule II [10] Article III Rule 6 [11] Article IV Rule 5(a) [12] Article 3 Rule 8 and Article V, but see Article VI [13] Goode R., Commercial Law (2nd Ed) p.902. [14] Dromgoole S. & Baatz Y “Interest in Goods” (2nd Ed) Chapter 22 [15] The Carso 1930 AMC 1740 at p. 1758 (S.D. N.Y. 1930). [16] Tetley, W. “Letters of Indemnity at Shipment and Letters of Guarantee at Discharge” [17] Tetley,W. Marine Cargo Claims, 3rd Ed., Editions Yvon Blais, Montreal, 1988, at 821. [18] Standard Chartered Bank v. Pakistan National Shipping Corporation and Others (№2) [1998] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 684 at 688 (Q.B. Com Ct.). Lord Justice Evans, comments regarding Cresswell, J.’s statement in the Court of Appeal decision, approved with the assertions and additionally remarked: “This requirement of honest commerce is stringently enforced by the English Courts. If a false bill of lading is knowingly issued by the master or agent of the shipowner, and if the claimant was intended to rely on it and did rely upon it and as a result of doing so has suffered loss, then the shipowner is liable in damages for the tort of deceit”. (Standard Chartered Bank v. Pakistan National Shipping Corporation and Others (№2) (C.A.), supra note 1, at 221). See also Howard, T. & Davenport, B. “English Maritime Law Update 1994/95” (1996) 27 J. Mar. L. & Com. 427. [19] Hazelwood, S.J. P & I Clubs: Law and Practice, 3rd Ed., LLP, London, 2000 at 179. [20] Ibid. [21] Standard Chartered Bank v Pakistan Nation Shipping Corporation and Others (№2) (C.A.); Hunter Grain v. Hyundai (1993) 117 ALR 507 (Federal Court of Australia). [22] Art. 3(4) of the Protocol to Amend the International Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules of Law Relating to Bills of Lading, Brussels, 23rd February, 1968 [the Hague/Visby Rules]. [23] Art. 16(3)(b). [24] Pomerene Bills of Lading Act (United States), 1916, 49 U.S. Code 102, addresses the practice of antedating. Section 22, protects parties who have relied on the date in the bill of lading to their detriment. It is uncommon for statute to include such protections. [25] The Stone Gemini [26] Pacific Carriers v BNP Paribas (High Court of Australia 5th Aug 2004) [27] Collern & Co. v China Ocean Shipping Company [1993] P&I International 16 [28] Carriage of Goods by Sea Act 1992, Section 2.2(a) [29] The Stettin (1889) 14 P.D. 142; The Sormorskiy 3068 [1994] 2 Lloyds Rep. 266 {deals where the bill is mislaid}. [30] Motis Exports v Dampskisselskabett AF 1912 [1999] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. Affirmed [2000] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 211 [31] Pacific Carriers v BNP Paribas [32] P&I Clubs (or Protection and Indemnity Clubs) are covered later in this paper in more detail. [33] The Stone Gemini [1999] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 255 (Federal Court of Australia) [34] Leamthong v Artis [2004] EWHC 2226 [35] Tetley, W [2004] ETL 287–344 [36] See Hunter Grain v. Hyundai; Brown, Jenkinson & Co. v. Percy Dalton; Standard Chartered Bank v. Pakistan National Shipping; St. Paul Fire and Marine Ins v. Typin Steel. [37] Brown, Jenkinson & Co., v. Percy Dalton, the court held that a letter of indemnity contract was illegal and unenforceable as the object of the contract was to commit a tort. See Hellenic Lines, Ltd. v. Chemoleum Corp. 1971 AMC 2605 (N.Y. Supr. Ct. App. Div), the majority of the court held that indemnity agreements are against to public policy and thus are not enforceable. [38] See Brown, Jenkinson & Co. v. Percy Dalton, & Hellenic Lines, Ltd. v. Chemoleum Corp. [39] See Shanghai Ocean-going Shipping Co. v. Xiamen Foreign Trade Co. recapitulated by Chen, at 92. [40] Protection and Indemnity Clubs [41] Gyselen, L. “P&I Insurance: The European Commission’s Decision Concerning the Agreement of the International Group of P&I Clubs,” in Marine Insurance at the Turn of the Millennium. M. Huybrechts (Ed.) Intersentia, Antwerpen, 1999, 181, at 181. [42] Ibid., at 182. [43] Tetley, W. International Maritime and Admiralty Law, Editions Yvon Blais, Montreal, 2002, at 591. [44] Luddenke, at 36. [45] Hazelwood, at 179. [46] Ibid. The American Steamship Owners Mutual Protection and Indemnity Association Form Policy, encompasses cargo liability in stipulation 7, but specifically excludes ante-dating in provision 7(g): “(7) Liability for loss of or damage to or in connection with cargo or other property (except mail or parcels post), including baggage and personal effects of passengers, to be carried, carried or which has been carried on board the insured vessel. Provided, however, that no liability shall exist hereunder for: …(g) Loss, damage or expense arising from the intentional issuance of bills of lading prior to receipt of the goods described therein, or covering goods not received at all.” [47] Hazelwood, at 179–180. [48] The Stone Gemini [1999] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 255, at 266 (Australian Federal Court. NSW). [49] Tetley at 824. [50] Ibid. [51] Tetley, W [2004] ETL 287–344 [52] Hare, J. Shipping Law & Admiralty Jurisdiction in South Africa, Junta & Co., Cape Town, 1999, at 459. [53] Ibid., In the United States, the documentary credit is generally refered to as a ‘letter of credit’. [54] Wilson, J. Carriage of Goods by Sea, 4th Ed. Longman, England, 2001, at 140. [55] Ibid., at 140–141. [56] Hare, at 459. [57] Uniform Customs and Practice for Documentary Credits, 1993 Revision, International Chamber of Commerce Publication №500. A text of UCP 500 can be found at the site: http://www.iccwbo.org/. In the US, the Uniform Commercial Code, regulates documentary credits in a manner similar to that of the UCP 500. [58] UCP 500, ibid., Art. 32. [59] See Standard Chartered Bank v. Pakistan Nation Shipping Corporation and Others (№2) (C.A.). [60] In Standard Chartered Bank v. Pakistan Nation Shipping Corporation and Others (№2) (C.A.), the carrier was held liable in the tort of deceit for antedating bills of lading in exchange for a letter of indemnity. The Court held that the carrier would have no defence to the bank’s claim, who was the holder of the bill of lading, and that the carrier was held to the same standard of commercial honesty that was required form the other parties to the letter of credit transaction. [61] Parker, B. “Liability for Incorrectly Clausing Bills of Lading” [2003] LMCLQ 201, at 205. For example see Brown Jenkinson v Percy Dalton, discussing fraudulent misrepresentation with regard to the issuance of clean bills of lading in exchange for letters of indemnity. For cases dealing generally with the tort of negligence and the tort of deceit, see The Saudi Crown [1986] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 261 (Q.B. Adm. Ct), Standard Chartered Bank v. Pakistan National Shipping Corporation and Others (№2) (C.A), and Hedley Byrne & Co. Ltd. v. Heller & Partners Ltd. [1963] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 485 (H.L.). [62] Ibid., at 258. The 1994 regulations that required ‘fairness’ were the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1994 (U.K). [63] ICC International Maritime Bureau, “A Profile on Maritime Fraud”, August 1982. [64] Ibid., at 252, citing Nicholas, B. “The Obligation to Disclose Information” in D.R. Harris and D. Tallon, Contract Law Today, Oxford, 1989, 166. The obligation to inform, or the obligation to disclose, arises most commonly in English law in the context of the question of “whether…a right to rescind [a contract] should arise where a contracting party had failed to disclose information that would have affected the other party’s decision to enter the contract.” There are, unique instances in English law where a duty to disclose does arise; Beatson, Anson’s Law of Contract, Oxford, 1998, at 257–269. [65] [1985] AC 424, at 439. [66] Ibbetson, at 252, taking special note of Beatson, J. “Has the Common Law a Future”[1997] CLJ 291, at 303–307. [67] Hunter Grain v. Hyundai, holding the carrier responsible for accepting a letter of indemnity in exchange for a clean bill of lading. [68] Ibid. See also Brown Jenkinson v. Percy Dalton, Standard Chartered Bank v. Pakistan Nation Shipping Corporation and Others (№2) (C.A.) supra note 1; United Baltic Corp. v. Dundee Perth & London Shipping Co. (1928) 32 Ll. L. Rep. 272, where the practice of issuing letters of indemnity was criticized by the court, with Wright J. using particularly strong language at p. 272: “The practice of issuing clean bills of lading when goods are damaged is very reprehensible. It leads to trouble, and the people who do it ought to suffer.” [69] See Tetley, “Chapter 38: Letters of Indemnity and of Guarantee” at 821, who, at p. 823, states that “letters of indemnity should not be condoned, by the courts, or by commerce, rather they should be discouraged.” See also Hazelwood, at 178. [70] See Brown Jenkinson v. Percy Dalton, supra note 1, where the Court of Appeal held that the indemnity was unenforceable because it was an illegal contract, with the purpose of perpetrating fraud on the buyer. See also the Hamburg Rules, which dictate in Article 17.3 that the carrier will have no right of indemnity against the shipper if his intention in issuing the clean bill of lading was to defraud a third party, including a consignee, who acts in reliance on the description of the goods in the bill of lading. [71] UNCTAD 2003 [72] Tetley, at 824. See also Bokalli, at 118, framing the problem from the point of view of the insurance companies, who, once the good have arrived damaged, pay out and then are subrogated into the rights of the consignees. These firms are often left without recourse as the carrier claims that the damage falls into one of the exculpatory provisions. [73] In Xiamen Special Zone Jijian Trade Co. v. Tianjing Ocean Shipping Co. (reported by Xia Chen, “Chinese Law on Carriage of Goods by Sea under Bills of Lading” (1999) 8 Currents Int’l Trade L. J. 89, at 93.) the consignee suspected fraud in the form of antedated bills of lading, however the evidence was not sufficient to unequivocally prove the fraud. The consignee then obtained a court order that mandated that the vessel provide all information related to the loading, and the Court itself also undertook its own investigation. Upon completion of the investigations, the Court held that there was in fact fraud and the carrier was liable. In commentary on the above decision, it has been noted that it is “often not easy for a cargo consignee to prove such fraud between the shipper and the carrier without having been present at the time of loading. [In the above case] the petitioner obtained the court’s order to preserve evidence on board the vessel, in addition to interviewing the vessel’s officials and other crew members and inspecting the cargo by professionals. In the meantime the court also launched an investigation of its own in accordance with Article 74 of the Law of Civil Procedure which provides that when there exists a danger that evidence may disappear or when it is difficult to gather evidence, the parties involved may petition the court for an order to preserve evidence and the court may also initiate its own efforts in preserving the evidence.” (Ibid., at 93). [74] Derry v. Peek (1889) 14 A.C. 337 (H.L.) at 374. [75] Standard Chartered Bank v. Pakistan National Shipping Corporation and Others (№2), at 224. See also Gaskell, N. Bills of Lading: Law and Contracts, LLP, London, 2000 at 179: “…the act of knowingly issuing a false bill of lading is an intentional deceit or fraud.” [76] Standard Chartered Bank v Pakistan National Shipping Corporation and Others (№2), ibid., at 221 and 224. [77] Tetley, W (2004) [2004] ETL 287–344